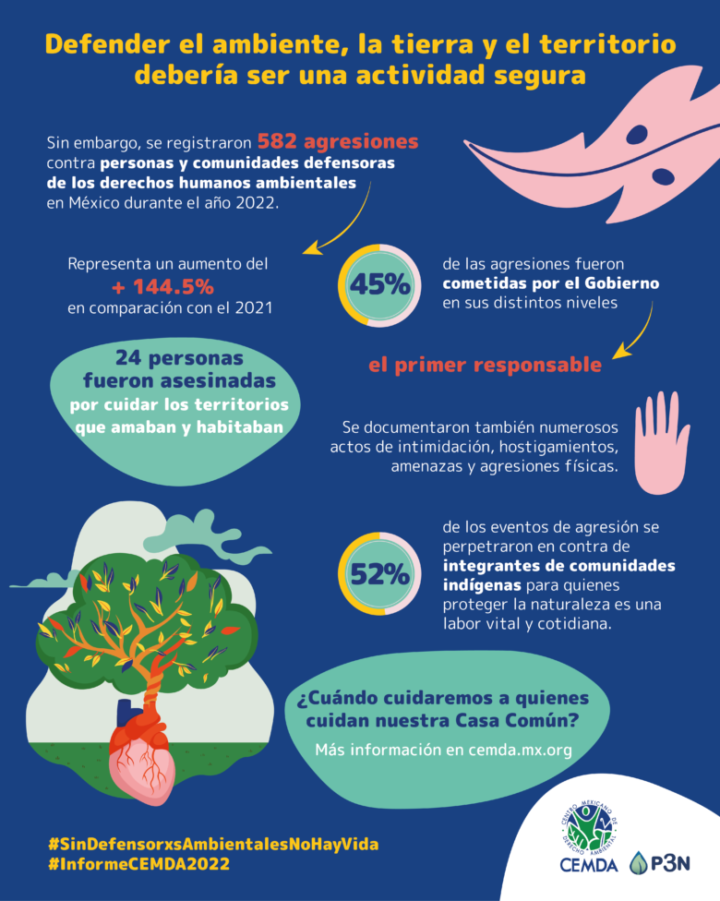

Civil Society, Conservation, Development & Aid, Economy & Trade, Editors’ Choice, Energy, Environment, Featured, Headlines, Human Rights, Indigenous Rights, Integration and Development Brazilian-style, Latin America & the Caribbean, Natural Resources, Projects, Regional Categories

Lacandona, the great Mayan jungle that extends through the state of Chiapas in southern Mexico, is home to natural wealth and indigenous peoples’ settlements that are once again threatened by the probable reactivation of abandoned oil wells. Image: Ceiba

– The Lacandona jungle in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas is home to 769 species of butterflies, 573 species of trees, 464 species of birds, 114 species of mammals, 119 species of amphibians and reptiles, and several abandoned oil wells.

The oil wells have been a source of concern for the communities of the great Mayan jungle and environmental organizations since the 1970s, when oil prospecting began in the area and gradually left at least five wells inactive, whether plugged or not.

“The situation is always complex, due to legal loopholes that do not delimit the jungle, the natural protected areas are not delimited, it has been a historical mess. The search for oil has always been there.” — Fermín Domínguez

Now, Mexico’s policy of increasing oil production, promoted by the federal government, is reviving the threat of reactivating oil industry activity in the jungle ecosystem of some 500,000 hectares located in the east of the state, which has lost 70 percent of its forest in recent decades due to deforestation.

A resident of the Benemérito de las Américas municipality, some 1,100 kilometers south of Mexico City, who requested anonymity for security reasons, told IPS that a Mexican oil services company has contacted some members of the ejidos – communities on formerly public land granted to farm individually or cooperatively – trying to buy land around the inactive wells.

“They say they are offering work. We are concerned that they are trying to restart oil exploration, because it is a natural area that could be damaged and already has problems,” he said.

Adjacent to Benemérito de las Américas, which has 23,603 inhabitants according to the latest records, the area where the inactive wells are located is within the 18,348 square kilometers of the protected Lacandona Jungle Region.

It is one of the seven reserves of the ecosystem that the Mexican government decreed in 2016 and where oil activity in its subsoil is banned.

Between 1903 and 2014, the state-owned oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) drilled five wells in the Lacandona jungle, inhabited by some 200,000 people, according to the autonomous governmental National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH), in charge of allocating hydrocarbon lots and approving oil and gas exploration plans. At least two of these deposits are now closed, according to the CNH.

The Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, in the Lacandona jungle in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, faces the threat of oil exploration, which would add to phenomena such as deforestation, drought and forest fires that have occurred in recent years. Image: Semarnat

The Lacantun well is located between a small group of houses and the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve (RBMA), the most megadiverse in the country, part of Lacandona and near the border with Guatemala. The CNH estimates the well’s proven oil reserves at 15.42 million barrels and gas reserves at 2.62 million cubic feet.

Chole, Tzeltal, Tzotzil and Lacandon Indians inhabit the jungle.

Other inactive deposits in the Benemérito de las Américas area are Cantil-101 and Bonampak-1, whose reserves are unknown.

In the rural areas of the municipality, the local population grows corn, beans and coffee and manages ecotourism sites. But violence has driven people out of Chiapas communities, as has been the case for weeks in the southern mountainous areas of the state due to border disputes and illegal business between criminal groups.

In addition, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), an indigenous organization that staged an uprising on Jan. 1, 1994 against the marginalization and poverty suffered by the native communities, is still present in the region.

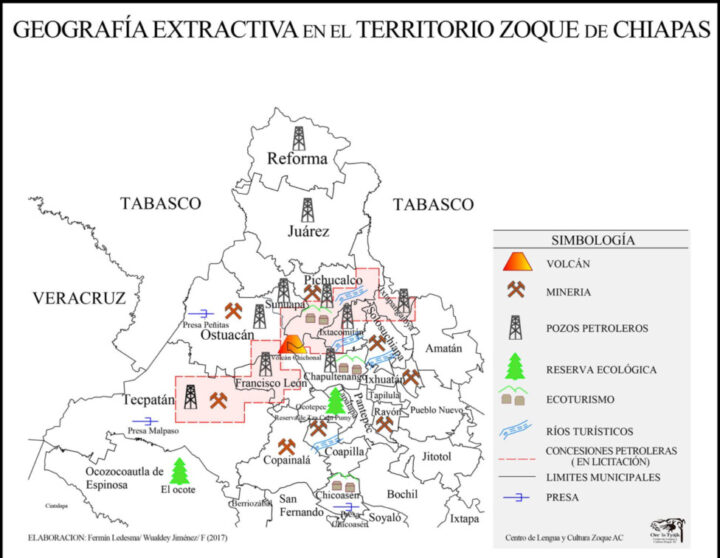

Chiapas, where oil was discovered at the beginning of the 20th century, is among the five main territories in terms of production of crude oil and gas in this Latin American country, with 10 hydrocarbon blocks in the northern strip of the state.

In November, Mexico extracted 1.64 million barrels of oil and 4.9 billion cubic feet of gas daily. The country currently ranks 20th in the world in terms of proven oil reserves and 41st in gas.

Historically, local communities have suffered water, soil and air pollution from Pemex operations.

As of November, there were 6,933 operational wells in the country, while Pemex has sealed 122 of the wells drilled since 2019, although none in Chiapas, according to a public information request filed by IPS.

Since taking office in December 2018, leftist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has strengthened Pemex and the also state-owned Federal Electricity Commission by promoting the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels, to the detriment of renewable energy.

The state of Chiapas is home to hydroelectric power plants, mining projects, hydrocarbon exploitation blocks and a section of the Mayan Train, the most emblematic megaproject of the current Mexican government. Image: Center for Zoque Language and Culture AC

Territory under siege

The RBMA is one of Mexico’s 225 natural protected areas (NPAs) and its 331,000 hectares are home to 20 percent of the country’s plant species, 30 percent of its birds, 27 percent of its mammals and 17 percent of its freshwater fish.

Like all of the Lacandona rainforest, the RBMA faces deforestation, the expansion of cattle ranching, wildlife trafficking, drought, and forest fires.

Fermín Ledesma, an academic at the public Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, said possible oil exploration could aggravate existing social and environmental conflicts in the state, in addition to growing criminal violence and the historical absence of the State.

“The situation is always complex, due to legal loopholes that do not delimit the jungle, the natural protected areas are not delimited, it has been a historical mess. The search for oil has always been there,” he told IPS from Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the capital of Chiapas.

The researcher said “it is a very complex area, with a 50-year agrarian conflict between indigenous peoples, often generated by the government itself, which created an overlapping of plans and lands.”

Ledesma pointed to a contradiction between the idea of PNAs that are depopulated in order to protect them and the historical presence of native peoples.

From 2001 to 2022, Chiapas lost 748,000 hectares of tree cover, equivalent to a 15 percent decrease since 2000, one of the largest sites of deforestation in Mexico, according to the international monitoring platform Global Forest Watch. In 2022 alone, 26,800 hectares of natural forest disappeared.

In addition, this state, one of the most impoverished in the country, has suffered from the presence of mining, the construction of three hydroelectric plants and, now, the Mayan Train, the Mexican government’s most emblematic megaproject inaugurated on Dec. 15, one of the seven sections of which runs through the north of the state.

But there are also stories of local resistance against oil production. In 2017, Zoque indigenous people prevented the auction of two blocks on some 84,000 hectares in nine municipalities that sought to obtain 437.8 million barrels of crude oil equivalent.

The anonymous source expressed hope for a repeat of that victory and highlighted the argument of conducting an indigenous consultation prior to the projects, free of pressure and with the fullest possible information. “With that we can stop the wells, as occurred in 2017. We are not going to let them move forward,” he said.

Ledesma the researcher questioned the argument of local development driven by natural resource extraction and territorial degradation as a pretext.

“They say it’s the only way to do it, but that’s not true. It leaves a trail of environmental damage, damage to human health, present and future damage. It is much easier for the population to accept compensation or give up the land, because they see it is degraded. A narrative is created that they live in an impoverished area and therefore they have to relocate. This has happened in other areas,” he said.