Active Citizens, Civil Society, Development & Aid, Economy & Trade, Editors’ Choice, Energy, Environment, Featured, Headlines, Integration and Development Brazilian-style, Latin America & the Caribbean, Projects, Regional Categories

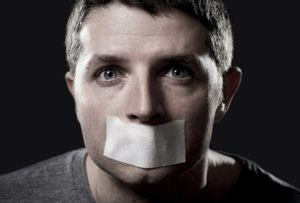

Demonstrators demand clarification of the murder of land rights activist Samir Flores and the shutdown of a thermoelectric plant in the state of Morelos, in central Mexico, in a February 2019 protest on Mexico City’s emblematic Paseo Reforma. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy/IPS

– Since 2012, Teresa Castellanos has fought the construction of a gas-fired power plant in Huexca, in the central Mexican state of Morelos, adjacent to the country’s capital.

“We don’t want the power plant to operate, because it will cause irreparable damage, polluting the water and air. This project was imposed on us; we have to defend the water and the land. This is not an industrial zone,” the activist, coordinator of the Huexca Resistance Committee, told IPS.

During the tests, the constant noise of the turbines also altered the life of this small community of just over 1,000 people, mostly farmers, near the Cuautla River, within the rural municipality of Yecapixtla.

“Development banks must have safeguards and principles for sustainable investment. National regulations are needed, which define climate finance and green finance, what principles govern them, what are the climate risks. The trend should be to increasingly finance green projects and less and less hydrocarbons.” — Liliana Estrada

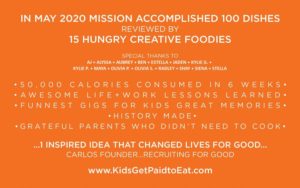

The Central Combined Cycle Plant, located in Huexca and with a capacity of 620 megawatts based on gas and steam, is part of the Morelos Integral Project (PIM), developed by the state Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). It also consists of an aqueduct and a gas pipeline that crosses the states of Morelos, Puebla and Tlaxcala.

The People’s Front in Defence of Land and Water of Morelos, Puebla and Tlaxcala and its ally, the Permanent Assembly of the People of Morelos, have managed to get several court orders that have blocked the operation of the plant, the 12-km aqueduct and the 171-km gas pipeline since 2015.

Castellanos, who has won an international and a national award for her activism, has been involved in the battle against the plant from the very start, which has earned her persecution and threats.

The opposition to the power plant by local communities that depend on planting corn, beans, squash and tomatoes and raising cattle and pigs, focuses on the lack of consultation, the threat to their agricultural activity, due to the extraction of water from the rivers, and the discharge of liquid waste.

In February 2019, a public consultation that did not meet international standards supported the completion of the project.

A few days earlier, activist Samir Flores had been murdered, a crime that remains unsolved – just one more instance of violence against environmentalists in Mexico. Despite Flores’ murder, the government of leftist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador went ahead with the referendum and upheld the result.

Public funds have fuelled the conflict, as the state-owned National Bank of Public Works and Services (Banobras) lent some 55 million dollars for the pipeline.

As in the case of other projects, development banks have become a financial pillar for the oil industry in Latin America’s second-largest nation, population 130 million.

The National Bank of Foreign Trade (Bancomext), Banobras and Nacional Financiera (Nafin) have funneled millions of dollars into building pipelines and oil and gas facilities in recent years, even though the climate change crisis makes it necessary to abandon such investments.

They have also financed renewable energy projects, but in much smaller amounts than fossil fuels.

The construction and operation of the Central Combined Cycle Plant, of the state Federal Electricity Commission, financed with public funds, unleashed a conflict with residents of Huexca, a small community in the central Mexican state of Morelos, which has brought the operation of the thermoelectric plant to a halt. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy/IPS

Energy reform pillar

The energy reform that then conservative president Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018) enacted in 2013 opened the sector to private capital, broke the monopoly of the state-owned Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) oil giant and CFE, and made Mexico an attractive market for international investment in the sector.

To support this transformation, the state development banks also opened their coffers.´

Since 2012, Banobras, which finances infrastructure and public works and services, has lent at least 721 million dollars for the construction of gas pipelines, 10.2 billion dollars for oil and gas projects, 251 million dollars for electrical cogeneration, from steam generated in hydrocarbon plants, and eight million dollars for the construction of a thermoelectric plant that will burn fuel oil in the northwestern state of Baja California Sur.

Bancomext, which provides financing to exporters, importers and nine strategic sectors, has delivered some 500,000 dollars to oil companies in the eastern state of Tamaulipas and another 446 million dollars in Mexico City. It has also provided 65.4 million dollars to gas initiatives in the northern state of Nuevo Leon and 626.7 million dollars in Mexico City.

In addition, it has contributed 1.5 billion dollars for the supply of gas through pipelines to the final consumer; 324 million dollars for the extraction of oil and gas; 216 million dollars for the construction of public works for oil and gas; 126 million dollars for the manufacture of products derived from oil and coal; nearly seven million dollars for oil refining; 0.65 million dollars for the commercialisation of fuels; 0.25 million dollars for the drilling and maintenance of hydrocarbon wells; as well as 0.25 million dollars for oil platform maintenance and services.

In February, Bancomext granted a loan of 7.1 million dollars to Grupo Diarqco, in what it presented as the first credit to a private Mexican company in the industry, to exploit an oil field in the southeastern state of Tabasco.

Nafin, which grants credits and guarantees to public and private projects, created in 2014 the Energy Impulse Programme for these initiatives, endowed with more than a billion dollars.

It also manages, along with the economy ministry, the Public Trust to Promote the Development of Energy Industry National Suppliers and Contractors, designed for the industrial promotion of local production chains and direct investment in the energy industry, which this year has a fund of some 41 million dollars.

Missing: social and environmental safeguards

As in the case of the Morelos Integral Project, the gas pipelines have been a source of conflict with local communities, arising from the lack of socio-environmental safeguards and standards to guarantee that a project and its financing will respect the human rights of potentially affected communities.

Nafin and Banobras lack such safeguards, while Bacomext has had an “Environmental and Social Risk Management System Guide” since 2017, with no evidence of whether and how it has been applied to energy projects financed since then.

Since 2003, three platforms of international standards have emerged, to which Mexico’s development banks have not adhered, on human rights; social and environmental assessments and impacts; the application of safeguards; stakeholder participation; complaint resolution; and transparency.

The planet needs 80 percent of the global hydrocarbon reserves to stay underground in order for the temperature increase to remain at 1.5 degrees Celsius, as set out in the Paris Agreement on climate change.

The treaty, signed by 196 countries and territories in 2015, will enter into force at year-end and is considered indispensable to avoid irreversible climate disasters and human catastrophes.

Liliana Estrada, a researcher with the Climate Finance Group of Latin America and the Caribbean, told IPS that most investment in energy still goes to fossil fuels.

“After the reform, they have to enter into strategic projects and follow the guidelines of the government; they cannot go against these strategic lines. The gas and gas pipelines became strategic,” with the boost to the megaprojects of the López Obrador administration, said the representative of this coalition of non-governmental organisations and academics.

These credits are part of the fossil fuel subsidies that Mexico has pledged, to several international bodies, to eliminate.

The Mexican energy industry has also attracted international private banks, which have lent 55.95 billion dollars to 12 corporations, according to “Banking on Climate Change: Fossil Fuel Finance Report 2020”, released in March by six international environmental organisations.

The CFE received some 5.4 billion dollars from 12 banks between 2016 and 2019, and Pemex received 48.3 billion dollars from 20 foreign banks.

Based on Huexca’s experience, Castellanos demanded that these investments be stopped.

“If it’s our company, as the government says, then we can close it down. We have to defend the space in which we live, because we only have one planet and it belongs to all of us, it belongs to every living being, and it is our obligation to contribute something to this planet, because we are only here for a short while, we are guests of the earth”, she said.

Estrada called for sustainable financing regulations and questioned the lack of government leadership in this regard.

“Development banks must have safeguards and principles for sustainable investment,” she said. “National regulations are needed, which define climate finance and green finance, what principles govern them, what are the climate risks. The trend should be to increasingly finance green projects and less and less hydrocarbons.”