Active Citizens, Civil Society, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Headlines, Human Rights, Latin America & the Caribbean, Migration & Refugees, Population, Poverty & SDGs, Regional Categories

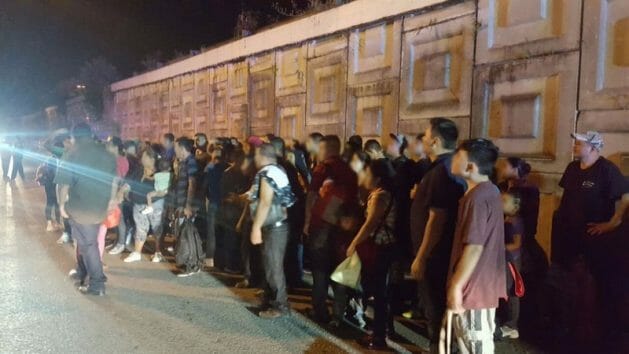

A hundred Central American migrants were rescued from an overcrowded trailer truck in the Mexican state of Tabasco. It has been impossible to stop people from making the hazardous journey of thousands of kilometers to the United States due to the lack of opportunities in their countries of origin. CREDIT: Mesoamerican Migrant Movement

– The immigration agreement reached in Los Angeles, California at the end of the Summit of the Americas, hosted by U.S. President Joe Biden, raises more questions than answers and the likelihood that once again there will be more noise than actual benefits for migrants, especially Central Americans.

And immigration was once again the main issue discussed at the Jul. 12 bilateral meeting between Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Biden at the White House.

At the meeting, López Obrador asked Biden to facilitate the entry of “more skilled” Mexican and Central American workers into the U.S. “to support” the economy and help curb irregular migration.

Central American analysts told IPS that it is generally positive that immigration was addressed at the June summit and that concrete commitments were reached. But they also agreed that much remains to be done to tackle the question of undocumented migration.

That is especially true considering that the leaders of the three Central American nations generating a massive flow of poor people who risk their lives to reach the United States, largely without papers, were absent from the meeting.

Just as the Ninth Summit of the Americas was getting underway on Jun. 6 in Los Angeles, an undocumented 15-year-old Salvadoran migrant began her journey alone to the United States, with New York as her final destination.

She left her native San Juan Opico, in the department of La Libertad in central El Salvador.

“We communicate every day, she tells me that she is in Tamaulipas, Mexico, and that everything is going well according to plan. They give them food and they are not mistreating her, but they don’t let her leave the safe houses,” Omar Martinez, the Salvadoran uncle of the migrant girl, whose name he preferred not to mention, told IPS.

She was able to make the journey because her mother, who is waiting for her in New York, managed to save the 15,000-dollar cost of the trip, led as always by a guide or “coyote”, as they are known in Central America, who in turn form part of networks in Guatemala and Mexico that smuggle people across the border between Mexico and the United States.

The meeting of presidents in Los Angeles “was marked by the issue of temporary jobs, and the presidents of key Central American countries were absent, so there was a vacuum in that regard,” researcher Silvia Raquec Cum, of Guatemala’s Pop No’j Association, told IPS.

In fact, neither the presidents of Honduras, Xiomara Castro, of Guatemala, Alejandro Giammattei, or El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, attended the conclave due to political friction with the United States, in a political snub that would have been hard to imagine just a few years ago.

Other Latin American presidents boycotted the Summit of the Americas as an act of protest, such as Mexico’s López Obrador, precisely because Washington did not invite the leaders of Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela, which it considers dictatorships.

From rural communities like this one, the village of Huisisilapa in the municipality of San Pablo Tacachico in central El Salvador, where there are few possibilities of finding work, many people set out for the United States, often without documents, in search of the “American dream”. CREDIT: Edgardo Ayala/IPS

More temporary jobs

Promoting more temporary jobs is one of the commitments of the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection adopted at the Summit of the Americas and signed by some twenty heads of state on Jun. 10 in that U.S. city.

“Temporary jobs are an important issue, but let’s remember that economic questions are not the only way to address migration. Not all migration is driven by economic reasons, there are also situations of insecurity and other causes,” Raquec Cum emphasized.

Moreover, these temporary jobs do not allow the beneficiaries to stay and settle in the country; they have to return to their places of origin, where their lives could be at risk.

“It is good that they (the temporary jobs) are being created and are expanding, but we must be aware that the beneficiaries are only workers, they are not allowed to settle down, and there are people who for various reasons no longer want to return to their countries,” researcher Danilo Rivera, of the Central American Institute of Social and Development Studies, told IPS from the Guatemalan capital.

The Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection states that it “seeks to mobilize the entire region around bold actions that will transform our approach to managing migration in the Americas.”

The Declaration is based on four pillars: stability and assistance for communities; expansion of legal pathways; humane migration management; and coordinated emergency response.

The focus on expanding legal pathways includes Canada, which plans to receive more than 50,000 agricultural workers from Mexico, Guatemala and the Caribbean in 2022.

While Mexico will expand the Border Worker Card program to include 10,000 to 20,000 more beneficiaries, it is also offering another plan to create job opportunities in Mexico for 15,000 to 20,000 workers from Guatemala each year.

The United States, for its part, is committed to a 65 million dollar pilot program to help U.S. farmers hire temporary agricultural workers, who receive H-2A visas.

“It is necessary to rethink governments’ capacity to promote regular migration based on temporary work programs when it is clear that there is not enough labor power to cover the great needs in terms of employment demands,” said Rivera from Guatemala.

He added that despite the effort put forth by the presidents at the summit, there is no mention at all of the comprehensive reform that has been offered for several years to legalize some 11 million immigrants who arrived in the United States without documents.

A reform bill to that effect is currently stalled in the U.S. Congress.

Many of the 11 million undocumented migrants in the United States come from Central America, especially Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, as well as Mexico.

While the idea of immigration reform is not moving forward in Congress, more than 60 percent of the undocumented migrants have lived in the country for over a decade and have more than four million U.S.-born children, the New York Times reported in January 2021.

This population group represents five percent of the workforce in the agriculture, construction and hospitality sectors, the report added.

Despite the risks involved in undertaking the irregular, undocumented journey to the United States, many Salvadorans continue to make the trip, and many are deported, such as the people seen in this photo taken at a registration center after they were sent back to San Salvador. CREDIT: Edgardo Ayala/IPS

More political asylum

The Declaration also includes another important component of the migration agreement: a commitment to strengthen political asylum programs.

For example, among other agreements in this area, Canada will increase the resettlement of refugees from the Americas and aims to receive up to 4,000 people by 2028, the Declaration states.

For its part, the United States will commit to resettle 20,000 refugees from the Americas during fiscal years 2023 and 2024.

“What I took away from the summit is the question of creating a pathway to address the issue of refugees in the countries of origin,” Karen Valladares, of the National Forum for Migration in Honduras, told IPS from Tegucigalpa.

She added: “In the case of Honduras, we are having a lot of extra-regional and extra-continental population traffic.”

Valladares said that while it is important “to enable refugee processes for people passing through our country, we must remember that Honduras is not seen as a destination, but as a transit country.”

Raquec Cum, of the Pop No’j Association in Guatemala, said “They were also talking about the extension of visas for refugees, but the bottom line is how they are going to carry out this process; there are specific points that were signed and to which they committed themselves, but the how is what needs to be developed.”

Meanwhile, the Salvadoran teenager en route to New York has told her uncle that she expects to get there in about a month.

“She left because she wants to better herself, to improve her situation, because in El Salvador it is expensive to live,” said Omar, the girl’s uncle.

“I have even thought about leaving the country, but I suffer from respiratory problems and could not run a lot or swim, for example, and sometimes you have to run away from the migra (border patrol),” he said.