Armed Conflicts, Asia-Pacific, Civil Society, Global Governance, Headlines, Human Rights, Middle East & North Africa

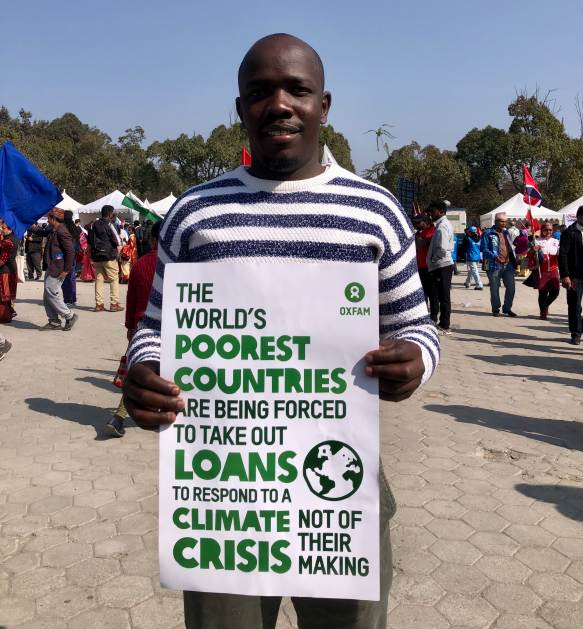

Protesting against Israel’s attacks on Gaza, at the opening day march of the World Social Forum in Kathmandu. Credit: Marty Logan/IPS

– Romi Ghimire has a busy life running a non-profit organization dedicated to Nepal’s rural people, but she also feels driven to do something about Gaza. “There are a lot of issues happening in the world, but right now the genocide in Gaza is the most urgent one,” she said inside the Palestine tent at the World Social Forum (WSF) in Kathmandu on Saturday.

“We’re watching it live…. we’re seeing it on a daily basis: every morning and evening I’m consuming it and I just can’t stop thinking about it. I can’t pretend that it isn’t happening,” Ghimire told IPS. “We have to raise awareness about it around the world because we are all the (Palestinians) have. They don’t have any arms or ammunition, any military — it’s just people like us that they have.”

“People like us” include the roughly 30,000 activists expected to attend the WSF, the annual global gathering of social activists, happening this year in Nepal’s capital Kathmandu until Monday. This block of the city centre is bustling with activists, rushing to reach a scheduled workshop or bumping shoulders with peers from 90+ countries amid white tents set up as temporary classrooms in a fairground.

Israel’s ongoing assault on Gaza, in response to an attack on Israel by Hamas on Oct. 7, 2023, is one of the most discussed issues.

On Friday, Dr Varsen Aghabekian spoke to 30 activists from Nepal, South Asia and beyond. The former Commissioner General for the Palestinian Independent Commission for Human Rights, Aghabekian detailed the history that has culminated in Israel’s occupation of Palestine, stressing the deep roots of the current assaults.

Demographic strategy

For example, in Mandate Palestine (as it was known in 1947), Palestinians made up 93% of the population and Jewish people were 7%. By 2023 the make-up had changed dramatically, with Palestinians at 51% and the Jewish population equal to 49%, said Aghabekian, labelling the process part of Israel’s “erasure”.

Historical “annexation” includes takeover of public and private property. In 1947, 90% of such property was owned by Palestinians; by 2023 they had been relegated to 22% of historic Palestine.

Israeli laws and policies “institutionalize the superiority and privilege the status of Jews,” added Aghabekian. They reserve the right of self-determination in Israel exclusively for the Jewish people, and declare Hebrew as the official state language, demoting Arabic, which had been the country’s official second language.

“We rightfully call (the situation) apartheid but when we do that many western countries frown and say: ‘It can’t be!’… Israel is trying to project that an occupier state is a victim of our resistance and our violence (but) we have the right to resist as an occupied people who want to be liberated.”

Eventually Israel must make peace with the Palestinians, added Aghabekian. “If they are prospering and we are in pain there will not be peace. The Gaza genocide, despite its disasters, is an opportunity… even the US said seriously ‘maybe we should think about the two-state solution’. I think we’re moving toward that.”

Not only is Israel misrepresenting its occupation and current attack on Gaza, the situation has revealed the hypocrisy of western legal, religious and cultural tradition, argued Mitri Raheb, the first president of Dar-al-Kalima University in Bethlehem, who spoke after Aghabekian.

Israel’s response to the Hamas attack has revealed the “warrior God,” not the God of peace, said Raheb, citing a personal example. A German bishop he met counselled Palestinians to remain non-violent. But just weeks later Raheb, who also served as the pastor of the Christmas Lutheran Church in Bethlehem from 1987 until 2017, saw the bishop on TV calling for western countries to provide Ukraine with tanks to counter Russia’s invasion.

Palestinians, he added, used to “believe in and fight for human rights because we thought they were international, they were for everyone. But I’m starting to question that. I think that human rights were meant for white Europeans, so they won’t kill each other any more, but it’s OK if the rest of the world is killed by the empire.”

“Business of colonialism”

Legal expert Wasem Ahmad dissected the economic structure that props up Israel’s occupation. “Israel has refined the art of colonization through what I call the best business practice of colonialism, which invites multinational actors and corporations to invest in their colonial project. And that provides an economic incentive to ensure that political positions are supportive of Israel.”

A human rights scholar, Ahmad told IPS he recognizes the limitations of the human rights system. “The more you do this work the more cynical you become of the system as it’s proposed. (Human rights) look very nice on paper but when you try to put them into practice you realize that there are a lot of political obstacles to that realization and it has to do with the broader imperial interests at play.”

“Our role,” he continued, “is to push that system and engage it, and force the wheels of justice to turn. Either it works in our benefit or we expose it and over time that system will change, even if it requires a breakdown to rebuild.”

But opposing Israel’s colonization through the legal system is only one approach, added Ahmad. “The idea that I’m only going to rely on the legal mechanisms, ignoring that the law is a social construct connected to economic, political and cultural interests and beliefs in society ignores that reality.”

Despite his critique of the West’s legal and cultural traditions, Raheb said he was invigorated by the throngs of people worldwide, and at the WSF, protesting Israel’s attacks. “Gaza was the wake-up call for all of us. And I think in the future this will just get stronger and stronger… Gaza galvanized the global South because it was the magnifying glass: suddenly we could see clearly. That was the turning point.”