Asia-Pacific, Civil Society, Headlines, Health

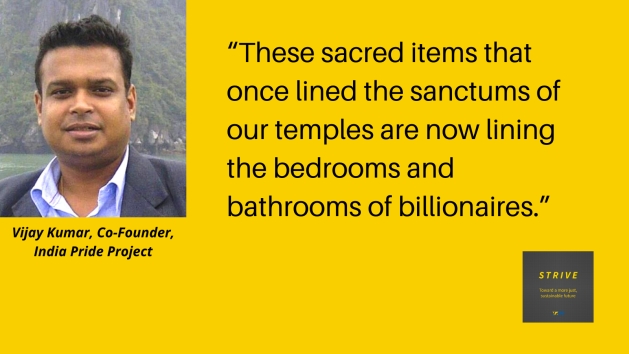

During the pandemic, there was little support from the government when it came to making funding and resources available to the nonprofits that were working closely with communities. | Picture courtesy: Digital Empowerment Foundation

– From its devastating economic impact and the migrant crisis to the startling death toll, the COVID-19 pandemic in India unfurled one crisis after the other. The glaring gaps in our system, which had always been there, became even more prominent during the pandemic. There is one question at the back of everyone’s mind that still remains unanswered: What went wrong?

No entity can operate in isolation, be it the government, the private sector, or civil society. During times of crisis, the government must ensure that all cogs in the wheel continue to work effectively. Civil society—local communities and nonprofits—must enable delivery of public services up until the last mile. And, finally, the private sector needs to step up in terms of financial resources and leveraging of networks and influence.

However, when the pandemic was at its peak in India, these three entities failed to come together and work collaboratively to cushion the devastating effects of COVID-19 on the people.

The missing link between the government and the social sector

According to our village-level digital entrepreneurs in the SoochnaPreneur programme at Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF), the four essential systems that were massively hit by the pandemic were education, healthcare, finance, and citizen entitlements. When the pandemic was raging, our SoochnaPreneurs reported that all people wanted was food and rations, a device to access online education for their children, the ability to talk to a doctor or health worker to learn how to keep themselves safe, and to make some money to meet their daily needs from the confines of their homes. Ironically, given the stringent nature of the lockdowns, all this needed access to the internet.

However, across the country, lack of access to resources, high levels of digital illiteracy, and the deepening digital divide exacerbated by the pandemic acted as major roadblocks in India’s COVID-19 response. Even as the government announced relief packages—food grains and cash payments—the mechanisms of delivery to beneficiaries at the last mile were unclear.

For instance, common service centres (CSCs), which are supposed to work as access points that enable digital delivery of services such as banking and finance across rural India, were mostly non-functional. During the pandemic, the government claimed that people could use their local CSCs to access various digital services including telehealth and registration for vaccinations. However, like any other office, shop, or business centre, almost all CSCs had closed their operations due to the strict lockdown rules in various states.

With government services not always being available, the social sector stepped up. Whether it was making access to digital tools and digital literacy a priority or the distribution of essentials, nonprofits across the country filled in the gaps. According to one report, nonprofits in 13 states and union territories were able to provide meals to more people during the lockdown than the concerned state governments.

The question that arises is: Would a collaborative relationship between the government and the social sector have aided a better response to the COVID-19 crisis?

For instance, the distribution of food grains could have been made efficient from the get-go if, rather than having long queues of people waiting at shops, organisations with the digital know-how had been allowed to deliver ration at the doorsteps of people with a biometric machine in hand. This synchronisation and management of resources is something that should have been under the government’s purview, while a partnership with civil society organisations could have helped with execution and delivery. Considering that hundreds of thousands of nonprofits working at the grassroots were tasked as frontline workers, the government could have tapped into this already existing infrastructure and network.

The lack of trust between the social sector and the government didn’t help. During the pandemic, there was little support from the government when it came to making funding and resources available to the nonprofits that were working closely with communities. For instance, while local nonprofits worked as service providers during the pandemic, funds lying with local government bodies could have been diverted to their operations to successfully navigate the panic-like situation brought on by the first lockdown when everything came to a halt.

The Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Bill, 2020, also imposed difficult conditions on what could be considered eligible expenses for nonprofit organisations, thus creating more obstacles in raising and distributing crucial aid. Even as the prime minister called for nonprofits to step in, many organisations found their hands tied due to certain rules imposed in the middle of the pandemic.

Moreover, during the first lockdown, there was a diversion of CSR funds to PM Cares. At present, not only is there a lack of transparency on how these funds have been deployed, but this diversion of funds has also been a huge blow to nonprofits who have been struggling to look after their own employees and their organisations while providing relief to communities on the ground.

The private sector did not step up either

There was lack of communication and collaboration across business, and a piecemeal approach was adopted. Industry associations could have encouraged CEOs and company heads to interact with each other and solve issues on a larger scale. For instance, industry bodies such as the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI), and Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) could have deployed their resources to help manage the mass migration of workers from industrial towns and urban centres more systematically and humanely.

In pre-pandemic times, CSR within corporates would ask nonprofits to work in areas where they have manufacturing facilities and offer localised support. Corporates could have extended this reasoning during the lockdown as well and enlisted the support of their nonprofit partners to help those workers and informal sector migrants who were homebound, while providing the nonprofits with the required monetary and infrastructure support.

There was also a reluctance from corporates to innovate in times of need. Since DEF works on digital integration to fight poverty, we reached out to many CSR funders to provide funds for buying smartphones, tablets, projectors, and other electronic devices to provide digital infrastructure in the villages. However, it took us more than a year to convince some of them to help us offer support to people with no digital access and empowerment through our Digital Daan initiative.

It is important to contextualise the social and economic support at the time of disaster and that can happen only if there is a relationship of trust between the stakeholders.

What the social sector could have done better

The onset of the pandemic brought with it uncertainty for most nonprofits. In addition to lack of funding and overstretched resources, many nonprofits had to take up the role of relief workers and divert efforts from their primary objectives, which would have been domestic violence, child protection, water and sanitation, and so on.

One important factor missing in this entire conversation was the inability of many nonprofits to adopt digital tools to improve operations, efficiency, and delivery of services. While webinars became a recurring feature in their calendars, thus creating a space for knowledge sharing, grassroots nonprofits were often not a part of these dialogues. Smaller nonprofits were also overwhelmed with work on the ground due to the needs of their communities coupled with inadequate support from either their funders or governments; hence, many of them had little time or resources to think or build their capacity to go digital.

The pandemic did however push several nonprofits to adopt digital tools for operations and delivery of services. Larger nonprofits with their own networks, adequate funding, and a strong digital presence were able to leverage digital platforms. However, many of the smaller nonprofits and those at the frontlines had to innovate to reach beneficiaries digitally.

Moreover, with the government aggressively pushing Digital India—from telehealth to online education and even the vaccine roll-out—it became imperative for organisations to incorporate digital and technological solutions in their everyday operations. Many nonprofits therefore had to work on building in-house digital capacity and infrastructure during the pandemic, while also serving their communities and raising funds.

In the case of mobilising money, digital platforms could have been a powerful tool for the sector, and they did help many nonprofits raise funds. However, this was not the case for the entire social sector.

According to the India Giving Report 2021 by the Charities Aid Foundation, individual donations were at an all-time high during the pandemic. Crowdfunding platforms such as GiveIndia provided people easy access to donate to various causes. However, this giving may not have been as diversified—the absence of reliable information online acted as a barrier for many givers while donating. Therefore, givers may have chosen to stick to organisations they trusted. And many local nonprofits with limited digital know-how had to rely on local giving or local resource mobilisation.

For example, our colleague Mohamed Arif, whom we lost in the second wave, was in charge of DEF’s digital centre at Nuh, Haryana. He was digitally savvy and active on social media and was thus able to raise approximately INR 25 lakh (in cash and food grains, and other essentials) through his personal Facebook profile and networks.

However, while the pandemic did push many nonprofits to incorporate technology-led solutions, I find that urgency dwindling again. Digital empowerment of the sector requires sustained efforts wherein organisations put aside certain funds every year for digitally upskilling their employees, maintaining digital collaterals, and modifying their approach to include technology in their everyday operations.

I see the pandemic as an inflection point in the future of nonprofits and civil society as a whole. Which organisations survive this period of transition will largely depend on how well they can adapt to these changing times. According to me, one of the key changes the sector will have to make to stay relevant is to become more digitally aligned.

Osama Manzar, the author of this article, is the founder and director of Digital Empowerment Foundation. He is a Senior Ashoka Fellow, a Chevening Scholar, and has served on several boards such as the Association for Affordable Internet, Association of Progressive Communications, World Summit Awards, and Down To Earth. He specialises in creating digital models for poverty alleviation and has travelled to more than 10,000 villages. Get in touch with him on Twitter: @osamamanzar

This story was originally published by India Development Review (IDR)