Civil Society, Economy & Trade, Featured, Financial Crisis, Gender, Gender Identity, Headlines, Latin America & the Caribbean, TerraViva United Nations

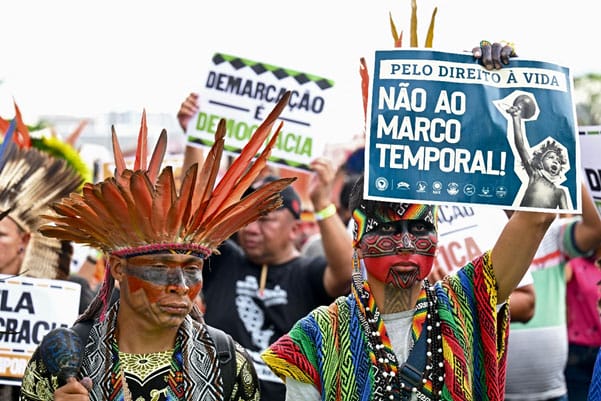

Credit: Tomás Cuesta/Getty Images

– For many of Argentina’s voters the choice in the 19 November presidential runoff is between the lesser of two evils: Sergio Massa, economy minister of a government that’s presiding over a once-in-a-generation economic meltdown with a whopping 140-per cent inflation rate, or Javier Milei, a far-right libertarian who admires Donald Trump, wants to shut down the Central Bank and wields a chainsaw in public as a symbol of his willingness to slash the state. Many will rue that it ever came to this.

A peculiar outsider

A post-modern media celebrity, Milei’s performance style is a perfect fit for social media. He’s easily angered, reacts violently and insults copiously. He’s unapologetically sexist and mocks identity politics.

Milei bangs the drum for ‘anarcho-capitalism’, an ultra-individualistic ideology in which the market has absolute pre-eminence: earlier this year, he described the sale of human organs as ‘just another market’.

To expand his appeal beyond this extreme economic niche he forged an alliance with the culturally conservative right. His running mate, Victoria Villarruel, represents the backlash against abortion – legalised after decades of civil society campaigning in 2020 – and sexual diversity and gender equality policies, along with reappraisal of the murderous military dictatorship that ruled Argentina between 1976 and 1983.

In the run-up to primary elections in August, the two mainstream coalitions – the centre-left incumbent Union for the Homeland (UP) and the centre-right opposition Together for Change (JxC) – displayed a notable lack of leadership and indulged in internal squabbles that showed very little empathy for people’s daily struggles. All they had to offer in the face of widespread concerns about inflation and insecurity were the candidacies of the current minister of the economy and a former minister of security. They made it easy for Milei to hold them responsible for decades of corruption, ineffectiveness and failure.

In Milei’s discourse, the hardworking, productive majority is being bled dry by taxation to maintain the privileges of a parasitic and corrupt political ‘caste’. His proposal is deceptively simple: shrink the state to a minimum to destroy the caste that lives off it, clearing their way for individual progress.

Milei gained traction among young voters, particularly young men, via TikTok. He found fertile ground among a generation that no longer expect to be better off than their parents. While many of his followers concede that his ideas may be a little crazy, they appear to be willing to take the risk of embracing the unknown on the basis that the really crazy plan would be to allow those long in control to retain their power and expect things to turn out differently. Milei has capitalised on the despair, hopelessness and accumulated anger so many rightfully feel.

Surprise after surprise

The first surprise came on 13 August, when Milei won the most votes of any candidate in the primaries.

Milei only entered politics in 2021, when the 17 per cent vote he amassed in the capital, Buenos Aires, sent him and two other libertarians to the National Congress. In the 2023 primaries he went much further, winning 30 per cent of the vote. He placed ahead of JxC, whose two candidates received a joint 28 per cent, and UP, the current incarnation of the Peronist Party, which took 27 per cent. The bulk of the UP vote, 21 per cent, went to Massa. That Peronism, once the dominant force, came third was a historic first.

The second surprise came on 22 October. Following the primaries, all talk was of Milei winning the presidency. He trumpeted his intent to win the first round outright. Measured against these expectations, his second place looks like an underperformance. But the fact that a candidate who wasn’t on the radar before the primaries has made the runoff shows how quickly the political landscape can shift.

In the October vote Milei took almost the exact share he’d received in the primaries. Massa finished above him with almost 37 per cent, displacing JxC, which lost four points on its second-place performance in the primaries.

The fact that the economy minister was able to distance himself from the government he’s part of – one often described as the worst in 40 years – to come first was viewed as a notable victory, even though his share was just about the lowest Peronism has ever received.

One explanation for Massa’s improved performance was turnout, which increased by eight points to almost 78 per cent – still low for a country with compulsory voting, but enough to make a difference. Much of the increase could be credited to the political machinery that mobilised voters on election day, aided by the minister-candidate pulling as many levers as he could to improve his chances. This included putting lots of instant cash into voters’ pockets, including through tax breaks benefiting targeted groups of workers and consumers.

An unpalatable decision

There’s still much uncertainty ahead. Economic failure is Milei’s best propaganda, so much will depend on how the economy behaves over the next couple of weeks. Milei and the destruction he represents can’t be written off.

Neither those currently in power nor those in the mainstream opposition recognise the obvious: Milei is their fault. They’ve held power for the best part of the past 40 years without effectively tackling any of the issues that concern people the most.

Many voters now feel they face an unpalatable choice between a corrupt and failing government and a dangerous disruptor. They fear that if they choose to keep Milei out, their votes may be misinterpreted as a show of active support for a continuity they also reject. What’s at stake here is more than one election. If Milei is kept at bay, the political dynamics leading to the current economic dysfunction will still need to be addressed – or the far-right threat to democracy won’t end with Milei.

Inés M. Pousadela is CIVICUS Senior Research Specialist, co-director and writer for CIVICUS Lens and co-author of the State of Civil Society Report.