Armed Conflicts, Civil Society, Climate Change, Crime & Justice, Development & Aid, Featured, Global, Headlines, Health, Human Rights, Inequality, Peace, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres addresses the 22nd session of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues at the General Assembly Hall of the United Nations headquarters in New York City on 17 April 17 2023. Credit: Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images

– This September, world leaders and public policy advocates from around the world will descend on New York for the UN General Assembly. Alongside conversations on peace and security, global development and climate change, progress – or the lack of it – on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is expected to take centre-stage. A major SDG Summit will be held on 18 and 19 September. The UN hopes that it will serve as a ‘rallying cry to recharge momentum for world leaders to come together to reflect on where we stand and resolve to do more’. But are the world’s leaders in a mood to uphold the UN’s purpose, and can the UN’s leadership rise to the occasion by resolutely addressing destructive behaviours?

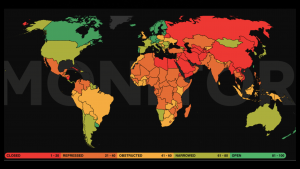

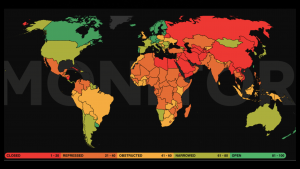

Sadly, the world is facing an acute crisis of leadership. In far too many countries authoritarian leaders have seized power through a combination of populist political discourse, outright repression and military coups. Our findings on the CIVICUS Monitor – a participatory research platform that measures civic freedoms in every country – show that 85% of the world’s population live in places where serious attacks on basic fundamental freedoms to organise, speak out and protest are taking place. Respect for these freedoms is essential so that people and civil society organisations can have a say in inclusive decision making.

UN undermined

The UN Charter begins with the words, ‘We the Peoples’ and a resolve to save future generations from the scourge of war. Its ideals, such as respect for human rights and the dignity of every person, are being eroded by powerful states that have introduced slippery concepts such as ‘cultural relativism’ and ‘development with national characteristics’. The consensus to seek solutions to global challenges through the UN appears to be at breaking point. As we speak hostilities are raging in Ukraine, Sudan, the Occupied Palestinian Territories and the Sahel region even as millions of people reel from the negative consequences of protracted conflicts and oppression in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Syria and Yemen, to name a few.

Article 1 of the UN Charter underscores the UN’s role in harmonising the actions of nations towards the attainment of common ends, including in relation to solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural or humanitarian character, and to promote respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms for all. But in a time of eye-watering inequality within and between countries, big economic decisions affecting people and the planet are not being made collectively at the UN but by the G20 group of the world’s biggest economies, whose leaders are meeting prior to the UN General Assembly to make economic decisions with ramifications for all countries.

Economic and development cooperation policies for a large chunk of the globe are also determined through the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Established in 1961, the OECD comprises 38 countries with a stated commitment to democratic values and market-based economics. Civil society has worked hard to get the OECD to take action on issues such as fair taxation, social protection and civic space.

More recently, the BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – grouping of countries that together account for 40 per cent of the world’s population and a quarter of the globe’s GDP are seeking to emerge as a counterweight to the OECD. However, concerns remain about the values that bind this alliance. At its recent summit in South Africa six new members were admitted, four of which – Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – are ruled by totalitarian governments with a history of repressing civil society voices. This comes on top of concerns that China and Russia are driving the BRICS agenda despite credible allegations that their governments have committed crimes against humanity.

The challenge before the UN’s leadership this September is to find ways to bring coherence and harmony to decisions being taken at the G20, OECD, BRICS and elsewhere to serve the best interests of excluded people around the globe. A focus on the SDGs by emphasising their universality and indivisibility can provide some hope.

SDGs off-track

The adoption of the SDGs in 2015 was a groundbreaking moment. The 17 ambitious SDGs and their 169 targets have been called the greatest ever human endeavour to create peaceful, just, equal and sustainable societies. The SDGs include promises to tackle inequality and corruption, promote women’s equality and empowerment, support inclusive and participatory governance, ensure sustainable consumption and production, usher in rule of law and catalyse effective partnerships for development.

But seven years on the SDGs are seriously off-track. The UN Secretary-General’s SDG progress report released this July laments that the promise to ‘leave no one behind’ is in peril. As many as 30 per cent of the targets are reported to have seen no progress or worse to have regressed below their 2015 baseline. The climate crisis, war in Ukraine, a weak global economy and the COVID-19 pandemic are cited as some of the reasons why progress is lacking.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres is pushing for an SDG stimulus plan to scale up financing to the tune of US$500 billion. It remains to be seen how successful this would be given the self-interest being pursued by major powers that have the financial resources to contribute. Moreover, without civic participation and guarantees for enabled civil societies, there is a high probability that SDG stimulus funds could be misused by authoritarian governments to reinforce networks of patronage and to shore up repressive state apparatuses.

Also up for discussion at the UN General Assembly will be plans for a major Summit for the Future in 2024 to deliver the UN Secretary-General’s Our Common Agenda report, released in 2021. This proposes among other things the appointment of a UN Envoy for Future Generations, an upgrade of key UN institutions, digital cooperation across the board and boosting partnerships to drive access and inclusion at the UN. But with multilateralism stymied by hostility and divisions among big powers on the implementation of internationally agreed norms, achieving progress on this agenda implies a huge responsibility on the UN’s leadership to forge consensus while speaking truth to power and challenging damaging behaviours by states and their leaders.

The UN’s leadership have found its voice on the issue of climate change. Secretary-General Guterres has been remarkably candid about the negative impacts of the fossil fuel industry and its supporters. This July, he warned that ‘The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived’. Similar candour is required to call out the twin plagues of authoritarianism and populism which are causing immense suffering to people around the world while exacerbating conflict, inequality and climate change.

The formation of the UN as the conscience of the world in 1945 was an exercise in optimism and altruism. This September that spirit will be needed more than ever to start creating a better world for all, and to prove the UN’s value.

Mandeep S. Tiwana is chief officer for evidence and engagement + representative to the UN headquarters at CIVICUS, the global civil society alliance.