Civil Society, Democracy, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Freedom of Expression, Headlines, Human Rights, Latin America & the Caribbean, Press Freedom, Regional Categories, TerraViva United Nations

Abigail Hernández (left) appears at a press conference with journalist Wendy Quintero, a member of Independent Journalists and Communicators of Nicaragua at the headquarters of the Nicaragua Nunca Más Rights Collective. CREDIT: José Mendieta / IPS

– Almost six years after the outbreak of the April 2018 protests, there are no signs left in Nicaragua of the violence that reigned in those days. There is no graffiti on walls or banners with demands or opinions against the leftist regime that has ruled the country since 2007.

Nor are there newspapers or opinion programs or debates on radio and television, let alone press conferences or public rallies.

“The Ortega and Murillo regime’s repressive mechanisms have escalated to dramatic and unimaginable levels. A simple opinion issued on social networks or a criticism of the regime could land you in jail or exile.” — Martha Irene Sánchez

The city of Managua, the capital, is always bustling and active, with markets and shopping malls open at all hours; traffic is usually disorderly and police patrols roam the streets and avenues at all times.

At noon every day, on all radio and television stations, the tired, quiet voice of Vice President Rosario Murillo is heard giving the government’s news, social achievements and propaganda messages such as phrases of love and praise to God.

The program, which has no specific name, is broadcast from Channel 4, the historical property of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), the ruling party, to which the other state media are linked. The private media outlets controlled by the presidential family are also connected, together with dozens of radio stations and portals on social networks.

It first emerged in 2007 as “a message from comrade Rosario, from the Communication and Citizenship Council of the People’s President.”

“Here we are, on Valentine’s Day, with love, friendship, and for us, love and peace, because it is with love and in peace that we can walk ahead, move forward, building the future of all, a fraternal future,” she said on Feb. 13.

Murillo has been Nicaragua’s vice president since she was appointed in 2016 by her husband, President Daniel Ortega, the veteran former guerrilla who has been in office since November 2006.

Murillo is also the regime’s spokesperson and the only authorized voice, among the population of 6.7 million inhabitants of this Central American country, who can speak publicly and freely about anything. No one else can do so.

Freedom of expression in Nicaragua is one of the most repressed and abused rights, said journalist Abigail Hernández, director of the Galería News platform.

Journalist and former political prisoner Lucía Pineda Úbau, together with Martha Sánchez, take part in a protest by Nicaraguan journalists exiled in Costa Rica. CREDIT: José Mendieta / IPS

Her opinion, tellingly sent via an encrypted messaging application, is based on experience: three years’ exile.

“The media and journalists are a good thermometer for measuring the quality of freedom of expression,” Hernández told IPS.

“When we have less and less access to sources of information, when they limit us from reporting from the streets, when we can’t take photos or videos freely, when we can’t do our work inside the country, it reveals that there is no freedom of expression,” she said.

She is part of a generation of 242 journalists who have had to go into exile since the 2018 protests, which began against Social Security reforms and ended in a bloodbath provoked by military and police forces, with more than 355 civilian deaths, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

Journalist Martha Irene Sánchez, director of the República 18 platform, holds similar views, also expressed from exile.

“The scenarios for exercising freedom of the press and freedom of expression in Nicaragua have not improved since 2018; on the contrary, we are encountering more and more hostility,” she told IPS.

She is also a member of Independent Journalists and Communicators of Nicaragua (PCIN), a union organization that emerged after the protests and all of whose members went into exile.

“The Ortega and Murillo regime’s repressive mechanisms have escalated to dramatic and unimaginable levels. A simple opinion issued on social networks or a criticism of the regime could land you in jail or exile,” Sánchez said.

A forum for the presentation of the report on freedom of expression and press freedom in Nicaragua, released in September 2023 in San José, Costa Rica. The panel included journalists from Nicaragua from the Connectas platform, including FLED director Guillermo Medrano, (second-right). CREDIT: José Mendieta / IPS

She cited the example of Victor Ticay, a local journalist in Nandaime, a municipality in the northwestern department of Granada, who went out one day to cover a procession during the Catholic Holy Week of 2023.

The event had not been authorized by the police, whose agents interrupted the religious ceremony and Ticay filmed the parishioners running away from the patrol cars through the streets of the town.

He was arrested, charged with treason and spreading false news and sentenced to eight years in prison.

Guillermo Medrano, director of the Foundation for Freedom of Expression and Democracy (FLED), explained to IPS that between 2020 and 2021, the Nicaraguan regime passed a series of laws criminalizing the practice of journalism and freedom of expression.

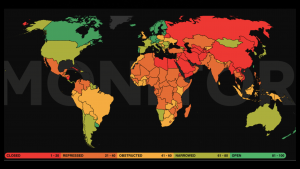

A study that FLED released in September 2023 in San José, Costa Rica, a country bordering Nicaragua and the center of the country’s exile community, documented 1329 press freedom violations, mostly perpetrated by state agents in the 2018-2023 five-year period.

The actions were taken against 338 Nicaraguan journalists and 78 media outlets, between April 2018 and April 2023.

They included the police intervention of several media outlets such as 100% Noticias, Confidencial, Trinchera de la Noticia, Radio Darío and La Prensa, the last newspaper circulating in Nicaragua until August 2022.

According to Medrano, the Special Law on Cybercrime, passed in October 2020, provides for prison sentences for the use of information “which in normal democracies should be freely accessible to citizens and the public.”

In theory, the main objective of this legislation is the prevention, investigation, prosecution and punishment of crimes committed by means of information and communication technologies to the detriment of natural or legal persons.

The press freedom advocate also pointed out that the Ortega-Murillo administration, which controls all state institutions and branches of power, as well as the security forces, established the Law for the Defense of the Rights of the People to Independence, Sovereignty and Self-Determination for Peace, effective since Dec. 22, 2020.

This law gives discretion to judges and prosecutors in terms of the crime of “treason”, which orders the banishment and denationalization of the accused, as well as life imprisonment through a reform of the penal system.

More than 180 people have already been prosecuted under these laws and at least 22 journalists were stripped of their citizenship and banished in 2023.

“Under these laws, freedom of speech and the press has become a high-risk constitutional right for those who exercise it within Nicaragua,” Medrano denounced.

A report by the regional organization Voces del Sur says that Nicaragua ended 2023 with new forms of repression and threats to press freedom applied through banishment, confiscations, illegal detentions and harassment and surveillance of the families of journalists working in exile.

The outlook, the report warns, is of greater silence about social issues.

Nicaraguan journalists conduct interviews under risk of persecution or criminalization, denounced several reporters in San José, Costa Rica, in August 2023. CREDIT: José Mendieta / IPS

According to the report, between 2018 and the end of 2022, 54 media outlets disappeared, including 31 radio stations, 15 television channels and eight print media outlets. Of that total, 16 media outlets were confiscated, including La Prensa, the country’s main daily newspaper.

“Sources, even under conditions of anonymity, are harder and harder to find, and the saddest thing is that the State, through its officials, continues to be the main victimizer of citizens’ rights of expression and journalists’ press rights,” Medrano complained.

The non-governmental Human Rights Collective Nicaragua Nunca Más, made up of human rights defenders and activists in exile, states that the Ortega-Murillo administration “has carried out an unprecedented attack on freedom of expression in this country.”

The organization reports that of 28 resolutions of precautionary measures for journalists in Latin America, which have been issued since 2018 by the IACHR on freedom of expression, 15 have been issued for Nicaragua.

However, it says that “none of the precautionary measures” have been complied with by the State and, on the contrary, harassment against the targets has increased.

“And that reveals to us the seriousness of the problem of a small country with disproportionate and unacceptable restrictions on fundamental freedoms,” said one of the agency’s advocates, on condition of anonymity for security reasons.

These complaints find no responses within Nicaragua, because with the exception of Murillo, no one is authorized to answer, but can simply repeat the official discourse: “Nicaragua lives in peace and security.”