The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews reminds Christians that they are surrounded by a great “cloud of witnesses.” (NRSV) That “cloud” has continued to grow in size since then. In this monthly column we will be thinking about some of the people and events, over the past 2000 years, that have helped make up this “cloud.” People and events that have helped build the community of the Christian church as it exists today.

The history of European colonisation, de-colonisation, and its aftermath, continues to prompt heated debate. In September 2022, a new temporary statue was placed on the Fourth Plinth in London’s historic Trafalgar Square, the fourteenth commission in the Mayor of London’s Fourth Plinth Programme.

Since 2003, the Fourth Plinth has showcased different pieces of artwork every two years. The plinth itself was originally intended to display a statue of King William IV, who reigned from 1830 to 37, but remained empty due to insufficient funds. Today it exhibits temporary artworks which are selected through public consultation and a commissioning group. Its past examples have included artworks as varied as: a dollop of whipped cream with an assortment of toppings; a recreation of a statue destroyed by ISIS; a child on a rocking horse; and a depiction of Nelson’s ship, HMS Victory, inside a large glass bottle stopped with a cork.

However, the installation which was placed there in 2022 (and which will remain there until 2024) provides an insight into an oft-forgotten period of British imperial history. It is entitled “Antelope,” and is the work of Samson Kambalu. The dramatic sculpture restages a photograph of two men which dates from 1914. The two men are Baptist preacher and pan-Africanist John Chilembwe and a European missionary named John Chorley. The photograph was taken outside Chilembwe’s church in Mbombwe village, in what is today southern Malawi.

As in the photograph, Chilembwe is wearing a hat. In so doing, he was defying the colonial convention that Africans should not wear hats in front of white people. It was a fashion convention which embodied political and social expectations that deference should be shown to whites.

There is, though, something more striking about the modern sculpture. This is that Chilembwe is depicted much larger than life, while Chorley is life-size. In fact, his statue stands at five metres, and towers over that of Chorley’s. The disparity is explained on the Mayor of London’s website: “By increasing his scale, the artist elevates Chilembwe and his story, revealing the hidden narratives of underrepresented peoples in the history of the British Empire in Africa, and beyond.”

Most people in the UK today will not previously have heard of John Chilembwe, but his history is intimately intertwined with that of British colonial rule in Africa and, also, with the impact of the First World War on that continent and its peoples.

The impact of the First World War on sub-Saharan Africa

In the popular shared memory of the First World War (1914-18) in the UK, it is largely remembered as a European conflict. The war on the Eastern Front usually only gets attention once we think of the Russian Revolution(s) of 1917. The fronts in Italy, and in the Balkans (where it started), are rarely mentioned. If attention moves beyond the Western Front, it rarely moves further than Gallipoli, with perhaps an excursion into the Middle East via memories of Lawrence of Arabia or imperial forces capturing Jerusalem from the Turks.

When it comes to sub-Saharan Africa, the conflict there rarely makes it onto the popular mental map of the war. And yet the impact of the war there was enormous, as the rival colonial powers fought out localised versions of the conflict which was tearing the European continent apart.

It has been estimated that over 250,000 African soldiers and porters, as well as approximately 750,000 African civilians, died in African campaigns that are largely unknown today outside of Africa. To get some idea of the scale of these casualties, it should be remembered that about 994,000 UK citizens (soldiers and civilians) died in that war.

As an aside, about 25% of the soldiers fighting for the British Crown in the First World War were Indians. But that is another – also often forgotten or sidelined – aspect of the war.

But to return to Africa. As well as the huge human cost, the war dislocated economies and societies in those areas on which it impacted. It also raised questions over the permanence of white European rule, since it was white European nations which were tearing each other apart; and whose attention was now occupied with fighting the conflict. For those within colonial populations already restless under colonial rule and economic exploitation, the war triggered anti-colonial activities. It was one of these that was led by John Chilembwe.

The Chilembwe uprising, 1915

Chilembwe was born sometime in the early 1870s (exact date unknown) and grew up in southern Malawi’s Chiradzulu District. There he was greatly influenced by the work and teaching of Christian missionaries. Among these was a radical missionary named Joseph Booth, whose outlook was summed up as: “Africa for Africans.”

With Booth, Chilembwe travelled to the US where he studied theology and saw, first hand, the struggle of black people for basic rights following the end of slavery. It was a struggle against white-controlled systems that were designed to keep them in a subservient place. This energised him to confront comparable colonial injustices in his homeland.

As an ordained Baptist minister, he established his own church within a context of black African agriculturalists being forced off their ancestral land in order to make room for white farmers. The poorly paid labour on these white-owned farms was carried out by landless black people. It was a land-rights issue replicated across the colonised world.

Chilembwe preached black advancement through hard work and education and was influenced by the ideas of the black American educator Booker T Washington. During the First World War there was huge recruitment of Africans to support the British forces in East Africa.

In Chilembwe’s region, large numbers of black Africans were taken to fight against the German army in what is now Tanzania. Others were employed as porters. Large numbers died of disease. Chilembwe opposed this recruitment and the conditions experienced by fellow Africans. He had earlier been shocked at the British colonial authorities’ lack of care for African refugees who had arrived in Malawi from neighbouring Mozambique, following a famine there which had occurred in 1913.

At the same time as he was beginning to agitate against the latest manifestation of colonial rule. African Christian millenarians in the region – encouraged by what appeared to be an apocalyptic conflict – were preaching that the war would lead to the end of white colonial rule.

Earlier, his mentor Booth had predicted that by 1914 European colonialism would end in Africa; following this, independent black nations would unite with black people in America in common cause against injustice. This was not, strictly speaking, an eschatological vision but it complemented it. However, Booth was a pacifist.

Taken together, it was a powerful mixture of suffering and hope. And the hope was deeply influenced by both gospel principles of the equality of all before God (a belief promoted, but with its social implications often defused, by missionary activity) and Christian end-times beliefs. After Chilembwe was defeated, the British colonial authorities accused him of wanting to create a theocratic state in the Malawian highlands, which suggests they read some millenarian aspirations in his actions.

In January 1915, Chilembwe and his followers rose up against the colonists. The uprising occurred in Nyasaland (modern Malawi). There were relatively few casualties among those attacked by his followers; but a number of white colonists were killed, even if (as some historians argue) Chilembwe was not directly involved in the killings.

Although Chilembwe was a member of the Chewa ethnic group, the brief rebellion pulled in support from several other ethnic groups, including the Yao, Lomwe, Nyanja, Chikunda, Ngoni and Tonga. This was consistent with other pan-African aspects of his life and ideology.

In response, the colonial forces rapidly mobilized. Facing defeat at the hands of the British, Chilembwe and a number of his followers tried to escape into Portuguese East Africa (modern Mozambique). However, many were captured. Following this, forty rebels were executed and 300 imprisoned. Chilembwe himself was shot dead by a police patrol (of fellow Africans, employed by the British) near the border.

The legacy of John Chilembwe

The placing of “Antelope” on the Fourth Plinth has triggered much debate, including explicit opposition. However, it is a fair guess that some of those who oppose its placing there accept the continued existence of statues of white colonists responsible for the subjection of black populations. It is likely that many of those who oppose the erecting of this statue would probably also resist the taking down of other statues. We live in contested times and history and commemoration are at the heart of this turbulence, as they are at the heart of much national myth-making.

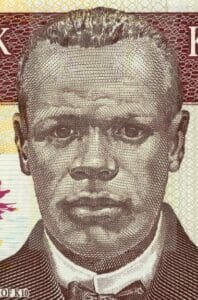

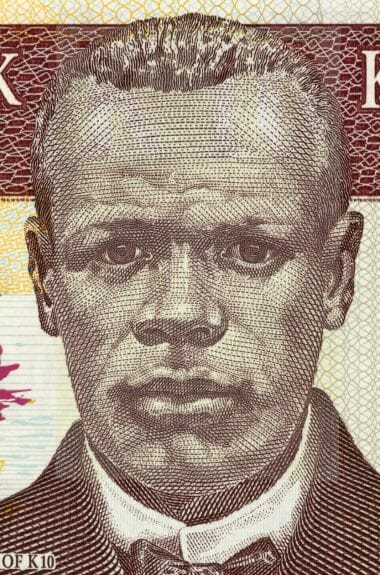

Chilembwe was one of the first to lead opposition to colonial rule in Africa. While his revolt was short-lived, its impact reverberated across the continent and among those of African descent living elsewhere under white colonial rule. Today, Chilembwe’s legacy can be seen across the modern state of Malawi. Several roads are named after him and his picture appears on the country’s currency (the kwacha), as well as on stamps. He even has an annual commemorative day and is seen, by many, as a founding figure in the fight for Malawian independence. However, some modern commentators – though recognising his importance – have argued that his uprising was premature and lacked the necessary groundwork of political activism required for resistance to colonial power.

Chilembwe is also considered by many commentators and historians to have influenced a number of later figures involved in black liberation. These include the Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey and John Langalibalele Dube, who was the founding president of what later became the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa.

What seems clear is that we should not separate Chilembwe’s political activism from his Christian background as a church leader and preacher. This clearly energised him, since he considered his actions expressed Christian opposition to racially-organised oppressive rule.

However we assess the rights and wrongs of his actions – and of the commemoration of him on the Fourth Plinth – Christian attitudes towards injustice must play a part within the assessment. This raises the very difficult question of what is an appropriate way to express opposition to systemic and powerful forces which subjugate and exploit people. This can make for uncomfortable discussions in our present age. But that these discussions need to take place seems indisputable. Perhaps we can reflect on that – whatever conclusions we reach – as we gaze at those two contrasting figures in Trafalgar Square.

Martyn Whittock is an evangelical historian and a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England. As an historian and author, or co-author, of fifty-five books, his work covers a wide range of historical and theological themes. In addition, as a commentator and columnist, he has written for several print and online news platforms; has been interviewed on TV and radio shows exploring the interaction of faith and politics; and appeared on Sky News discussing political events in the USA. Recently, he has been interviewed on several news platforms concerning faith and the Crown in the UK, and the war in Ukraine. His most recent books include: Trump and the Puritans (2020), The Secret History of Soviet Russia’s Police State (2020), Daughters of Eve (2021), Jesus the Unauthorized Biography (2021), The End Times, Again? (2021) and The Story of the Cross (2021). His latest book, Apocalyptic Politics (2022), explores the connection between end-times beliefs and radicalised politics across religions, time, and cultures.