Biodiversity, Climate Action, Climate Change, Conferences, COP30, Development & Aid, Economy & Trade, Energy, Environment, Global, Green Economy, Headlines, Labour, Natural Resources, TerraViva United Nations

As climate leaders gather in the Amazon, the world’s green transformation is speaking with a southern accent—powered by markets, technology, and a new economic logic.

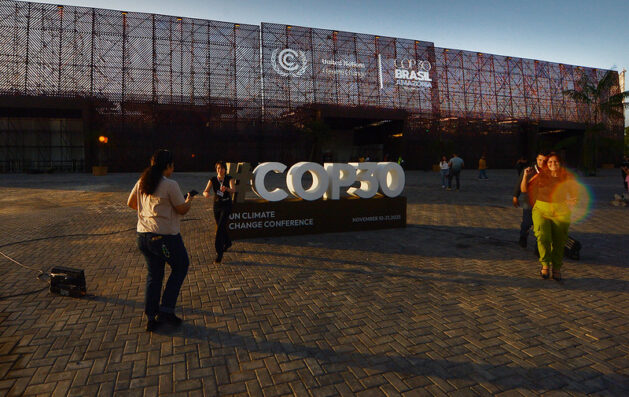

Belém—30th Conference of the Parties (COP30). Credit: Antônio Scorza/COP30

– When world leaders now gather in Belém, Brazil for the UN climate conference, expectations will be modest. Few believe the meeting will produce any breakthroughs. The United States is retreating from climate engagement. Europe is distracted. The UN is struggling to keep relevant in the 21st century.

But step outside the negotiation tents, and a different story unfolds—one of quiet revolutions, technological leaps, and a new geography of leadership. The green transformation of the world is no longer being designed in Western capitals. It is being built, at scale, in the Global South.

Ten years ago, anyone seeking inspiration on climate policy went to Brussels, Berlin or Paris. Today, you go to Beijing, Delhi or Jakarta. The center of gravity has shifted. China and India are now the twin engines of the global green economy, with Brazil, Vietnam and Indonesia closely behind.

Erik Solheim

This is not about rhetoric; it is about results. China accounts for roughly 60 percent of global capacity in solar, wind, and hydropower manufacturing. It dominates in electric vehicles, batteries, and high-speed rail. China’s 93 GW installation of solar in May 2025 is a historic high and exceeds the monthly or short‐term installation levels of any other country to date.

China has made the green transition its biggest business opportunity, turning green action into jobs, prosperity and global leadership. China is now making more money from exporting green technology than America makes from exporting fossil fuels.

India, too, is reshaping what green development looks like. I was in Andhra Pradesh last month, when I visited a wonderful six-gigawatt integrated energy park—solar, wind, and pumped storage. It delivers round-the-clock clean power. There is nothing like that in the West. In another state, Tamil Nadu, an ecotourism circuit is protecting mangroves and marine ecosystems while creating local jobs in tourism. The western state of Gujarat, long a laboratory for industrial innovation, has committed to 100 gigawatts of renewables by 2030, with the captains of Indian business – Adani and Reliance – driving large-scale solar and wind investments with the state government.

These are not pilot projects. They are national strategies. And they are succeeding because the economics have flipped.

The cost of solar power has fallen by over 90 percent in the last decade, largely thanks to the intense competition between Chinese solar companies. Battery storage is now competitive with fossil fuels. What was once an environmental aspiration has become a financial inevitability. In Indian Gujarat, solar-plus-storage projects are already cheaper than coal. Switching to clean energy is no longer a cost—it is a saving.

That is why climate action today is driven not by diplomacy, but by economics. The question is no longer if countries will go green, but who will own the technologies and industries that make it possible.

Europe, long the moral voice of the climate agenda, now risks losing the industrial race. After years of blocking imports from developing countries on grounds of “inferior” green quality, it now complains that Chinese electric vehicles are too good— too cheap and too efficient. Europe cannot have it both ways. The world cannot build a green transition behind protectionist walls. The markets must open to the best technologies, wherever they are made.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil understands this new reality. That is why he chose Belém, deep in the Amazon, as the site for climate talks. The location itself is a statement: the future of climate policy lies in protecting the rainforests and empowering the people who live within them.

Forests are not just carbon sinks; they are living economies. When I was Norway’s environment minister, we partnered with Brazil and Indonesia to reward them for reducing deforestation. Later, Guyana joined our effort—a small South American nation where nearly the entire population is of Indian or African origin.

Guyana has since turned conservation into currency. Under its jurisdictional REDD+ programme, the country now sells verified carbon credits through the global aviation market known as CORSIA. In the third quarter of this year, these credits traded at USD 22.55 per tonne of CO₂ equivalent, with around one million credits sold through a procurement event led by IATA and Mercuria.

The proceeds go directly to forest communities—building schools, improving digital access, and funding small enterprises. It is proof that the carbon market can deliver real value when tied to real lives. You cannot protect nature against the will of local people. You can only protect it with them. Last year in Guyana, I watched children play soccer and cricket beneath the jungle canopy—a glimpse of life thriving in harmony with the forest, not at its expense.

That, ultimately, is what Belém should represent: not another round of procedural debates, but a vision for linking markets, nature and livelihoods.

The Global South has also sidestepped one of the West’s greatest political failures: climate denial. In India, there is no major political party—or public figure, cricket star or Bollywood artist—questioning the reality of climate change. Leaders may differ on ideology, but not on this. Across Asia, from China to Indonesia, climate action unites rather than divides. Because here, ecology and economy move together.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India puts it simply: by going green, we also go prosperous. President Xi Jinping of China and President Lula of Brazil share that same message—a vision that draws people in, instead of lecturing them. It is this integration of growth and sustainability that explains why the Global South is moving faster than most of the developed world.

None of this means diplomacy is irrelevant. The UN still matters. But its institutions must evolve to reflect the realities of the 21st century. The Security Council, frozen in 1945, still excludes India and Africa from permanent membership. Without reform, multilateralism risks losing its meaning.

Yet, while negotiations stall, transformation continues. From solar parks in Gujarat to high-speed rail across China, from mangrove tourism in Tamil Nadu to carbon markets in Guyana—climate leadership is happening in real economies, not in press releases.

Belém will not deliver a grand agreement. But it doesn’t need to. The world is already moving—faster than our diplomats.

The story of Belem will not be written in communiqués, but in kilowatts, credits, and communities.

The real climate leaders are no longer in Washington or Brussels.

They are in Beijing, Delhi, São Paulo, and Georgetown.

The future of climate action is already here.

It just speaks with a southern accent.

The author is the former Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme and Norway’s Minister for Environment and International Development.

IPS UN Bureau