Active Citizens, Africa, Asia-Pacific, Civil Society, Democracy, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Green Economy, Headlines, Human Rights, Humanitarian Emergencies, Middle East & North Africa, Press Freedom, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

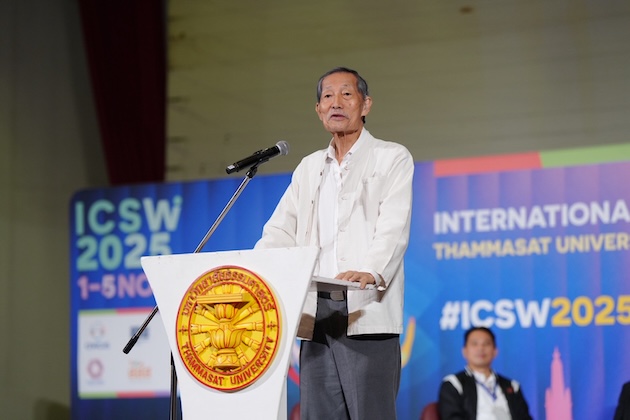

Secretary General of CIVICUS, Mandeep Tiwana, at International Civil Society Week 2025. Credit: Civicus

– It is a bleak global moment—with civil society actors battling assassinations, imprisonment, fabricated charges, and funding cuts to pro-democracy movements in a world gripped by inequality, climate chaos, and rising authoritarianism. Yet, the mood at Bangkok’s Thammasat University was anything but defeated.

Once the site of the 1976 massacre, where pro-democracy students were brutally crushed, the campus—a “hallowed ground” for civil society actors—echoed with renewed voices calling for defending democracy in what Secretary General of CIVICUS, Mandeep Tiwana, described as a “topsy-turvy world” with rising authoritarianism—a poignant reminder that even in places scarred by repression, the struggle for civic space endures.

“Let it resonate,” said Ichal Supriadi, Secretary General, Asian Democracy Network. “Democracy must be defended together,” adding that it was the “shared strength” that confronts authoritarianism.

Despite the hopeful spirit at Thammasat University, where the International Civil Society Week (ICSW) is underway, the conversations often turned to sobering realities. Dr. Gothom Arya of the Asian Cultural Forum on Development and the Peace and Culture Foundation reminded participants that civic freedoms are being curtailed across much of the world.

Citing alarming figures, he spoke bluntly of the global imbalance in priorities—noting how military expenditure continues to soar even as civic space shrinks. He pointedly referred to the United States’ Ministry of Defense as the “Ministry of War,” comparing its USD 968 billion military budget with China’s USD 3 billion and noting that spending on the war in Ukraine had increased tenfold in just three years—a stark illustration of global priorities. “This is where we are with respect to peace and war,” he said gloomily.

Ichal Supriadi, Secretary General, Asian Democracy Network. Credit: Civicus

At another session, similar reflections set the tone for a broader critique of global power dynamics. Walden Bello, a former senator and peace activist from the Philippines, argued that the United States—especially under the Trump administration—had abandoned even the pretense of a free-market system, replacing it with what he called “overt monopolistic hegemony.” American imperialism, he said, “graduated away from camouflage attempts and is now unapologetic in demanding that the world bend to its wishes.”

Dr. Gothom Arya of the Asian Cultural Forum on Development and the Peace and Culture Foundation. Credit: Civicus

Dr. Pervez Hoodbhoy, a Pakistani physicist and author, echoed the sentiment, expressing outrage at his own country’s leadership. He condemned Pakistan’s decision to nominate a “psychopath, habitual liar, and aggressive warmonger” for the Nobel Peace Prize, saying that the leadership had “no right to barter away minerals and rare earth materials to an American dictator” without public consent.

Hoodbhoy urged the international community to intervene and restart peace talks between Pakistan and India—two nuclear-armed neighbors perpetually teetering on the edge of renewed conflict.

But at no point during the day did the focus shift away from the ongoing humanitarian crises. Arya reminded the audience of the tragic loss of civilian lives in Gaza, the devastating fighting in Sudan that had led to widespread malnutrition, and the global inequality worsened by climate inaction. “Because some big countries refused to follow the Paris Agreement ten years ago,” he warned, “the rest of the world will suffer the consequences.”

That grim reality was brought into even sharper relief by Dr. Mustafa Barghouthi, a Palestinian physician and politician, who delivered a harrowing account of Gaza’s devastation. He said that through the use of American-supplied weapons, Israel had killed an estimated 12 percent of Gaza’s population, destroyed every hospital and university, and left nearly 10,000 bodies buried beneath the rubble.

“Even as these crises unfolded across the world, the conference demonstrated that civil society continues to persevere, as nearly 1,000 people from more than 75 organizations overcame travel bans and visa hurdles to gather at Thammasat University, sharing strategies, solidarity, and hope through over 120 sessions.

Among them was a delegation whose presence carried the weight of an entire nation’s silenced hopes—Hamrah, believed to be the only Afghan civil society group at ICSW.

“Our participation is important at a time when much of the world has turned its gaze away from Afghanistan,” Timor Sharan, co-founder and programme director of the HAMRAH Initiative, told IPS.

“It is vital to remind the global community that Afghan civil society has not disappeared; it’s fighting and holding the line.”

Through networks like HAMRAH, he said, activists, educators, and defenders have continued secret and online schools, documented abuses, and amplified those silenced under the Taliban rule. “Our presence here is both a statement of resilience and a call for solidarity.”

“Visibility matters,” pointed out Riska Carolina, an Indonesian woman and LGBTIQ+ rights advocate working with ASEAN SOGIE Caucus (ASC). “What’s even more powerful is being visible together.”

“It was special because it brought together movements—Dalit, Indigenous, feminist, disability, and queer—that rarely share the same space, creating room for intersectional democracy to take shape,” said Carolina, whose work focuses on regional advocacy for LGBTQIA+ rights within Southeast Asia’s political and human rights frameworks, especially the ASEAN system, which she said has historically been “slow to recognize issues of sexuality and gender diversity.”

“We work to make sure that SOGIESC (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Sex Characteristics) inclusion is not just seen as a niche issue, but as a core part of democracy, governance, and human rights. That means engaging governments, civil society, and regional bodies to ensure queer people’s participation, safety, and dignity is part of how we measure democratic progress.”

She said the ICSW provided ASC with a chance to make “visible” the connection between civic space, democracy, and queer liberation and to remind people that democracy is not only about elections but also about “who is able to live freely and who remains silenced by law or stigma.”

Away from the main sessions, civil society leaders gathered for a candid huddle—part reflection, part reckoning—to examine their role in an era when their space to act was shrinking.

“The dialogue surfaced some tough but necessary questions,” he said. They asked themselves: ‘Have we grasped the full scale of the challenges we face?’ ‘Are our responses strong enough?’ ‘Are we expecting anti-rights forces to respect our rules and values?’ ‘Are we reacting instead of setting the agenda? And are we allies—or accomplices—of those risking everything for justice?’

But if there was one thing crystal clear to everyone present, it was that civil society must stand united, not fragmented, to defend democracy.

IPS UN Bureau Report

The Angolan government’s 1 July decision to remove diesel subsidies, sharply pushing up public transport costs, triggered a series of

The Angolan government’s 1 July decision to remove diesel subsidies, sharply pushing up public transport costs, triggered a series of