Civil Society, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Poverty & SDGs, TerraViva United Nations

Maimunah Mohd Sharif is United Nations Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of UN-Habitat & Leilani Farha is the former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing, and Global Director of The Shift.

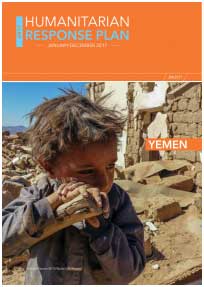

The Bijoy Sarani Railway Slum in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Credit: UNHabitat/Kirsten Milhahn

– Public health officials are calling the “stay home” policy the sacrifice of our generation. To flatten the curve of COVID-19 infections, this call of duty is now emblazoned on t-shirts, in street art and a celebrity hashtag.

But for the 1.8 billion people around the world living in homelessness and inadequate shelter, an appeal to “stay home” as an act of public health solidarity, is simply not possible. Such a call serves to highlight stark and long-standing inequalities in the housing market. It underscores that the human right to shelter is a life or death matter.

Throughout this global pandemic, governments are relying on access to adequate housing to slow the viral spread through self-isolating or social distancing policies. Yet, living conditions in poor or inadequate housing actually create a higher risk of infection whether from overcrowding which inhibits physical distancing or a lack of proper sanitation that makes regular hand-washing difficult.

At the most extreme, people experiencing homelessness must choose between sleeping rough or in shelters where physical distancing and adequate personal hygiene are almost impossible. Homeless populations and people living in inadequate housing often already suffer from chronic diseases and underlying conditions that make COVID-19 even more deadly.

It is now clear, housing is both prevention and cure – and a matter of life and death – in the face of COVID-19. Governments must take steps to protect people who are the most vulnerable to the pandemic by providing adequate shelter where it is lacking and ensuring the housed do not become homeless because of the economic consequences of the pandemic.

These crucial measures include stopping all evictions, postponing eviction court proceedings, prohibiting utility shut-offs and ensuring renters and mortgage payers do not accrue insurmountable debt during lockdowns.

In addition, vacant housing and hotel rooms should be allocated to people experiencing homelessness or fleeing domestic violence. Basic health care should be provided to people living in homelessness regardless of citizenship status and cash transfers should be established for people in urgent need.

Steps should be quickly taken to establish emergency handwashing facilities and health care services for at-risk and underserved communities and informal settlements.

In many cities and countries, emergency measures are already moving in this direction.

Berlin opened a hostel to temporarily house up to 200 homeless people, catering to all nationalities. The Welsh government pledged GBP10 million to local councils for emergency homeless housing by block booking empty lodging like hotels and student dormitories.

A woman outside a community run water facility in Old Town, Accra Ghana. Credit: UNHabitat/Kirsten Milhahn

In South Africa where under half of all households have access to basic handwashing facilities and in Kenya, where it is under a quarter of households, governments are increasing access to water for residents living in rural areas and informal settlements by providing water tanks, standpipes, and sanitation services in public spaces.

Many jurisdictions, such as Canada’s province of British Columbia, have suspended evictions. The eviction ban means landlords cannot issue a new notice to end a tenancy for any reason and existing orders will not be enforced.

Spain, France, the United Kingdom and the United States have announced mortgage postponements in an effort to curb potential defaults.

National and local governments are also working with the private sector to tackle housing issues. For example, Singaporean firms with government backing are providing accommodation for Malaysian workers who had been commuting to Singapore daily.

And as they are no tourists in Barcelona, the city has agreed with the Association of Barcelona Tourist Apartments to allocate 200 apartments for emergency housing for vulnerable families, homeless people and those affected by domestic violence.

Some cities are leveraging citizen solidarity. Residents of Los Angeles are making hand-washing stations for homeless people living in a depressed area known as Skid Row which are installed and maintained by a local community centre.

All of these urgent measures and more are desperately needed and demonstrate the way in which housing is inherently connected to our collective public health. These successful interventions also show concrete ways that governments and communities can effectively tackle the pre-existing global housing crisis – a crisis which affected at least 1.8 billion people worldwide, even before the pandemic.

In 2018 the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless reported that homelessness had skyrocketed across the continent. In the United States, 500,000 people are currently homeless, 40 per cent of whom are unsheltered.

In April last year, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) warned that rent is currently the biggest expense for households accounting on average for one-third of their income. In the last two decades, housing prices have grown three times faster than incomes.

The current global housing system treats housing as a commodity. In times of crisis, the inefficiencies of the market are clear with the public sector expected to absorb liabilities.

This is not sustainable and many cities are struggling to find shelter for their citizens. COVID-19 has brought into sharp relief the housing paradox – in a time when people are in n desperate need for shelter, apartments and houses sit empty. This market aberration needs correcting.

Governments are at a crossroads. They can treat COVID-19 as an acute emergency and address immediate needs without grappling with hard questions and fundamental questions about the global housing system.

Or they can take legislative and policy decisions to address immediate needs, while also addressing the present housing system’s structural inequalities, putting in place long term ‘rights-based’ solutions to address our collective right to adequate shelter. Housing must be affordable, accessible and adequate.

COVID-19 is unlikely to be the last pandemic or global crisis that we face. What we do now will shape the cities we live in, and how resilient we will be in the future.