Civil Society, Combating Desertification and Drought, Development & Aid, Economy & Trade, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Food & Agriculture, Green Economy, Headlines, Integration and Development Brazilian-style, Latin America & the Caribbean, Projects, Regional Categories, South-South, TerraViva United Nations, Water & Sanitation

Combating Desertification and Drought

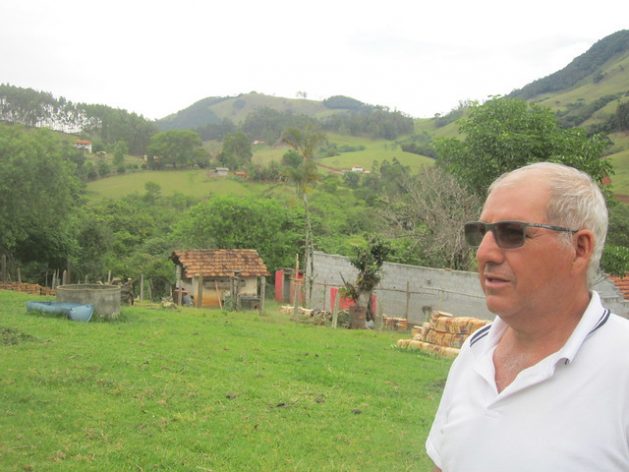

A rural settlement in the state of Pernambuco, in Brazil’s semiarid ecoregion. Tanks that collect rainwater from rooftops for drinking water and household usage have changed life in this parched land, where 1.1 million 16,000-litre tanks have been installed so far. CREDIT: Mario Osava/IPS

– After centuries of poverty, marginalisation from national development policies and a lack of support for positive local practices and projects, the semiarid regions of Latin America are preparing to forge their own agricultural paths by sharing knowledge, in a new and unprecedented initiative.

In Brazil’s semiarid Northeast, the Gran Chaco Americano, which is shared by Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay, and the Central American Dry Corridor (CADC), successful local practices will be identified, evaluated and documented to support the design of policies that promote climate change-resilient agriculture in the three ecoregions.

This is the objective of DAKI-Semiárido Vivo, an initiative financed by the United Nations International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and implemented by the Brazilian Semiarid Articulation (ASA), the Argentinean Foundation for Development in Justice and Peace (Fundapaz) and the National Development Foundation (Funde) of El Salvador.

DAKI stands for Dryland Adaptation Knowledge Initiative.

The project, launched on Aug. 18 in a special webinar where some of its creators were speakers, will last four years and involve 2,000 people, including public officials, rural extension agents, researchers and small farmers. Indirectly, 6,000 people will benefit from the training.

“The aim is to incorporate public officials from this field with the intention to influence the government’s actions,” said Antonio Barbosa, coordinator of DAKI-Semiárido Vivo and one of the leaders of the Brazilian organisation ASA.

The idea is to promote programmes that could benefit the three semiarid regions, which are home to at least 37 million people – more than the total populations of Chile, Ecuador and Peru combined.

The residents of semiarid regions, especially those who live in rural areas, face water scarcity aggravated by climate change, which affects their food security and quality of life.

Zulema Burneo, International Land Coalition coordinator for Latin America and the Caribbean and moderator of the webinar that launched the project, stressed that the initiative was aimed at “amplifying and strengthening” isolated efforts and a few longstanding collectives working on practices to improve life in semiarid areas.

Abel Manto, an inventor of technologies that he uses on his small farm in the state of Bahia, in Brazil’s semiarid ecoregion, holds up a watermelon while standing among the bean crop he is growing on top of an underground dam. The soil is on a waterproof plastic tarp that keeps near the surface the water that is retained by an underground dam. CREDIT: Mario Osava/IPS

The practices that represent the best knowledge of living in the drylands will be selected not so much for their technical aspects, but for the results achieved in terms of economic, ecological and social development, Barbosa explained to IPS in a telephone interview from the northeastern Brazilian city of Recife, where the headquarters of ASA are located.

After the process of systematisation of the best practices in each region is completed, harnessing traditional knowledge through exchanges between technicians and farmers, the next step will be “to build a methodology and the pedagogical content to be used in the training,” he said.

One result will be a platform for distance learning. The Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, also in Recife, will help with this.

Decentralised family or community water supply infrastructure, developed and disseminated by ASA, a network of 3,000 social organisations scattered throughout the Brazilian Northeast, is a key experience in this process.

In the 1.03 million square kilometres of drylands where 22 million Brazilians live, 38 percent in rural areas according to the 2010 census, 1.1 million rainwater harvesting tanks have been built so far for human consumption.

An estimated 350,000 more are needed to bring water to the entire rural population in the semiarid Northeast, said Barbosa.

But the most important aspect for agricultural development involves eight “technologies” for obtaining and storing water for crops and livestock. ASA, created in 1999, has helped install this infrastructure on 205,000 farms for this purpose and estimates that another 800 peasant families still need it.

There are farms that are too small to install the infrastructure, or that have other limitations, said Barbosa, who coordinates ASA’s One Land and Two Waters and native seed programmes.

The “calçadão” technique, where water runs down a sloping concrete terrace or even a road into a tank that has a capacity to hold 52,000 litres, is the most widely used system for irrigating vegetables.

A group of peasant farmers from El Salvador stand in front of one of the two rainwater tanks built in their village, La Colmena, in the municipality of Candelaria de la Frontera. The pond is part of a climate change adaptation project in the Central American Dry Corridor. Central American farmers like these and others from Brazil’s semiarid Northeast have exchanged experiences on solutions for living with lengthy droughts. CREDIT: Edgardo Ayala/IPS

And in Argentina’s Chaco region, 16,000-litre drinking water tanks are mushrooming.

But tanks for intensive and small farming irrigation are not suitable for the dry Chaco, where livestock is raised on large estates of hundreds of hectares, said Gabriel Seghezzo, executive director of Fundapaz, in an interview by phone with IPS from the city of Salta, capital of the province of the same name, one of those that make up Argentina’s Gran Chaco region.

“Here we need dams in the natural shallows and very deep wells; we have a serious water problem,” he said. “The groundwater is generally of poor quality, very salty or very deep.”

First, peasants and indigenous people face the problem of formalising ownership of their land, due to the lack of land titles. Then comes the challenge of access to water, both for household consumption and agricultural production.

“In some cases there is the possibility of diverting rivers. The Bermejo River overflows up to 60 km from its bed,” he said.

Currently there is an intense local drought, which seems to indicate a deterioration of the climate, urgently requiring adaptation and mitigation responses.

Reforestation and silvopastoral systems are good alternatives, in an area where deforestation is “the main conflict, due to the pressure of the advance of soy and corn monoculture and corporate cattle farming,” he said.

Mariano Barraza of the Wichí indigenous community (L) and Enzo Romero, a technician from the Fundapaz organisation, stand next to the tank built to store rainwater in an indigenous community in the province of Salta, in the Chaco ecoregion of northern Argentina, where there are six months of drought every year. CREDIT: Daniel Gutman/IPS

More forests would be beneficial for the water, reducing evaporation that is intense due to the heat and hot wind, he added.

Of the “technologies” developed in Brazil, one of the most useful for other semiarid regions is the “underground dam,” Claus Reiner, manager of IFAD programmes in Brazil, told IPS by phone from Brasilia.

The underground dam keeps the surrounding soil moist. It requires a certain amount of work to dig a long, deep trench along the drainage route of rainwater, where a plastic tarp is placed vertically, causing the water to pool during rainy periods. A location is chosen where the natural layer makes the dam impermeable from below.

This principle is important for the Central American Dry Corridor, where “the great challenge is how to infiltrate rainwater into the soil, in addition to collecting it for irrigation and human consumption,” said Ismael Merlos of El Salvador, founder of Funde and director of its Territorial Development Area.

The CADC, which cuts north to south through Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, is defined not as semiarid, but as a sub-humid region, because it rains slightly more there, although in an increasingly irregular manner.

Some solutions are not viable because “75 percent of the farming areas in the Corridor are sloping land, unprotected by organic material, which makes the water run off more quickly into the rivers,” Merlos told IPS by phone from San Salvador.

“In addition, the large irrigation systems that we’re familiar with are not accessible for the poor because of their high cost and the expensive energy for the extraction and pumping of water, from declining sources,” he said.

The most viable alternative, he added, is making better use of rainwater, by building tanks, or through techniques to retain moisture in the soil, such as reforestation and leaving straw and other harvest waste on the ground rather than burning it as peasant farmers continue to do.

“Harmful weather events, which four decades ago occurred one to three times a year, now happen 10 or more times a year, and their effects are more severe in the Dry Zone,” Merlos pointed out.

Funde is a Salvadoran centre for development research and policy formulation that together with Fundapaz, four Brazilian organisations forming part of the ASA network and seven other Latin American groups had been cooperating since 2013, when they created the Latin American Semiarid Platform.

The Platform paved the way for the DAKI-Semiárido Vivo which, using 78 percent of its two million dollar budget, opened up new horizons for synergy among Latin America’s semiarid ecoregions. To this end, said Burneo, it should create a virtuous alliance of “good practices and public policies.”