Civil Society, Combating Desertification and Drought, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Food & Agriculture, Human Rights, Indigenous Rights, Integration and Development Brazilian-style, Latin America & the Caribbean, Projects, Regional Categories, Water & Sanitation

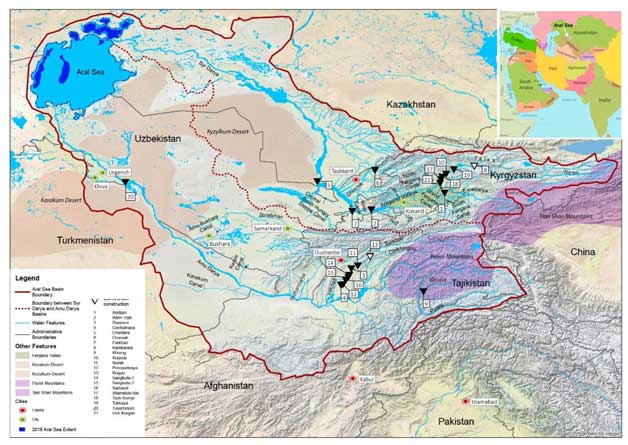

Long months of community work to install pipes to bring water from rock glaciers to indigenous villages in the Puna region in northwest Argentina served to strengthen collective organisation and community ties in an inhospitable ecoregion, where solidarity and joint efforts are essential to daily survival. Credit: Courtesy of Julio Sardina

– In Argentina’s Puna region, at 4,000 metres above sea level, the color green is rare in the arid landscape, which is dominated by different shades of brown and yellow. In this inhospitable environment, daily life has improved thanks to a system of piping water downhill from rock glaciers to local communities.

“When I was a girl we would walk an hour or two to fetch water from the hills. Since we didn’t have jerry cans or buckets, we carried it in sheepskin bags,” Viviana Gerónimo, a 50-year-old Kolla indigenous woman, tells IPS.

“We also built dams, to retain rainwater. We used it for ourselves and for our animals,” she adds. Gerónimo, a married mother of five, lives in Hornaditas de la Cordillera, an indigenous hamlet of just 15 families in the province of Jujuy in northwest Argentina, a few kilometres from the Bolivian border.

The Puna highlands region is a desert where only a few shrubs grow to less than half a metre in height and where it hardly ever rains – the average is around 200 millimetres a year, almost all of which falls in the southern hemisphere summer: December to March.

These high plateaus located above 3,000 metres altitude in the Andes mountains cover not only northwest Argentina but also northern Chile and southern Bolivia and Peru.

Local inhabitants in the Puna region depend mainly on livestock, although they cannot raise cows due to the poor quality of the pastures.

Geronimo’s family has 80 llamas and 120 sheep – the domestic species that best adapt to the climate of the Puna, although the profit margins are slim. In fact, the local indigenous people rarely shear them anymore because the wool fetches such low prices. They raise them for their own consumption and to sell the surplus meat.

Viviana Gerónimo adds color to the yellow and brown arid landscape of Hornaditas de la Cordillera, one of the Kolla indigenous communities that now have water for the consumption of the 15 local families and for their sheep, llamas and vicuñas, as well as subsistence crops, in this Andean highlands region in the northwest Argentine province of Jujuy. Credit: Daniel Gutman/IPS

The Kolla are the largest of the dozen or so indigenous peoples in Jujuy, where 7.8 percent of the population was recognised as native in the last national census in 2010 – more than three times the national figure of only 2.4 percent. Officially, there are 27,631 members of the Kolla people, although the real number is probably much higher, as there are more than 100 Kolla communities in the Puna.

Water brings change

The water collection system benefits the indigenous communities of Hornaditas de la Cordillera, Escobar Tres Cerritos and Cholacor, and the town of El Condor, the municipal seat, which has a primary and secondary school and first aid clinic.

El Cóndor is an hour’s drive from La Quiaca, the main Argentine city on the border with Bolivia. It has about 400 inhabitants, while the communities of the rest of the municipality number less than 100 people in all.

Climate change also seems to be playing its part in exacerbating the scarcity of water. “Although the biggest problem here has always been water, our grandparents said it used to rain more,” says 53-year-old Ricardo Tolaba, another resident of Hornaditas.

“In the past, the ponds, where underground water comes to the surface, dried up in June or July, after the summer rains. Now they dry up in March or April,” he told IPS.

The most important resource are the so-called rock glaciers: moving ice in the mountains covered in rocks and debris which keep them from melting; invisible but strategic water reserves.

The province of Jujuy has 255 rock glaciers, according to the National Glacier Inventory published by the Argentine government in 2018.

With government support, the local communities built a system of underground pipes that run down the slopes for 33 kilometres, using the force of gravity to pipe water to different villages.

“Back in 2007 we began to talk to the communities about how we could build a solution to the lack of water,” says agronomist Julio Sardina, a technician with the Secretariat of Family Agriculture who has worked with the indigenous settlements of Jujuy for more than 20 years.

Long months of community work to install pipes to bring water from rock glaciers to indigenous villages in the Puna region in northwest Argentina served to strengthen collective organisation and community ties in an inhospitable ecoregion, where solidarity and joint efforts are essential to daily survival. Credit: Courtesy of Julio Sardina

“The problem was that people in the lower-lying areas didn’t have water for their animals. And some wanted to plant crops but couldn’t because of the lack of water,” he adds during his tour with IPS through the different communities participating in the project, which are precariously connected by dirt roads in poor condition.

Sardina explains that the Secretariat of Family Agriculture provided the materials to build the system, thanks to funding from the Socioeconomic Inclusion in Rural Areas Project (Pisear), a national government programme.

From the outset, it was stipulated that the work had to be carried out by the members of the beneficiary communities.

“The project, besides bringing water to the villages, helped the communities organise and forge closer ties, since the families were isolated from each other,” says Sardina.

The system benefits some 600 people in an area where families are often nomadic, moving around to find the best pastures. Many Kolla Indians have communal land titles, which is not common among native peoples in Argentina.

When it reaches the communities, the water is stored in a tank. It is also piped to some of the houses and to water troughs for livestock.

But the greatest impact of the project was on agriculture, which has always been limited in the Puna region by the lack of water.

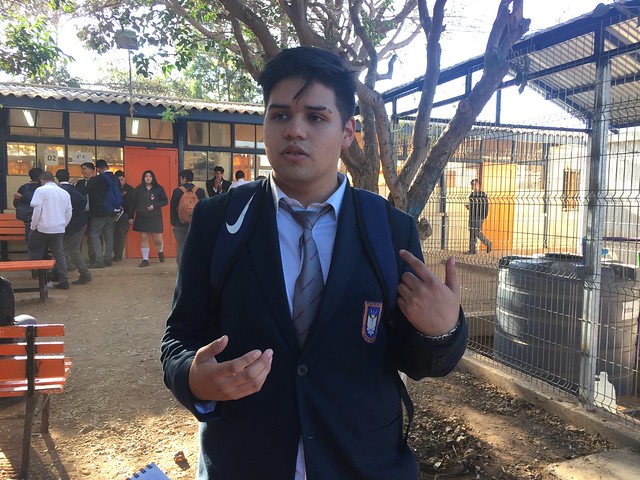

In the high Andean plateau of the Puna, in northwest Argentina, the biggest need was always water, says Ricardo Tolaba. People walked for hours to find it and carry it back in small containers, for human and animal consumption. With the new community-built system that pipes it from rock glaciers, “things began to change,” he adds. Credit: Daniel Gutman/IPS

David Quiquinte, also from Hornaditas, proudly relates that “a 40-centimetre-deep ditch was dug, where the pipe was buried to prevent freezing,” since in the wintertime temperatures in the Puna region can drop to 25 degrees Celsius below zero.

“For nearly six months, the entire community threw its effort into this work… except for one or two people,” the 40-year-old local resident told IPS, without concealing his irritation with those who didn’t help out.

During meetings with technicians from the Secretariat of Family Agriculture, the indigenous communities in Jujuy’s Puna region raised their concern about the growth of the population of vicuñas, a wild South American camelid native to the Andean highlands.

The vicuña came close to extinction in the 1960s, but recovered thanks to protection measures agreed by the countries of the Puna ecoregion.

“We needed water, especially because there wasn’t enough for the animals. And in the meetings about the water system project, many people complained that the vicuñas were eating the grass needed by the llamas and sheep,” Luis Gerónimo, 30, who lives in the community of Escobar Tres Cerritos, told IPS.

That is how the idea arose for training for the “chaccu”, an ancestral practice that the Kolla Indians have taken up again, as have other indigenous communities in Bolivia and Peru, which consists of capturing, shearing and releasing wild vicuñas.

“We’ve been practicing the chaccu for five years and people no longer see vicuñas as a problem. Today they are taken care of. The llamas and sheep graze in the lowlands and the hills are left to the vicuñas,” says Luis Gerónimo.

The chaccu and the water project pursue the same ultimate goal: to enable people from the communities to stay in Jujuy’s Puna region instead of migrating to the cities.

“I am one of the people who went to work in different parts of Argentina and came back. And I’m convinced that we have the resources to keep young people in the Puna,” says Tolaba.

He points out that “the main need in the Puna has always been water. Walking for hours to fetch water or to take the animals to drink are things we’ve been used to since we were kids here.”

But “with this project, things have begun to change,” he adds.