Armed Conflicts, Asia-Pacific, Civil Society, Development & Aid, Featured, Headlines, Human Rights, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Migration & Refugees, Religion, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations, Youth

Maung Sawyeddollah, Founder of the Rohingya Students Network, addresses the high-level conference of the General Assembly on the situation of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities in Myanmar Credit: UN Photo/Manuel Elías

– The international community convened for a high-level meeting at UN Headquarters, this time to mobilize political support for the ongoing issue of the persecution of the Rohingya Muslims and other minorities in Myanmar.

On Tuesday September 30, representatives from Rohingya advocacy groups, the UN system and member states convened at the General Assembly to address the ongoing challenges facing Rohingya Muslims and the broader context of the political and humanitarian situation in Myanmar.

UN President of the General Assembly Annalena Baerbock remarked that the conference was an opportunity to listen to stakeholders, notably civil society representatives with experience on the ground.

“Rohingya need the support of the international community, not just in words but in action,” she said.

Baerbock added there was an “urgent need for strengthened international solidarity and increased support,” and to make efforts to reach a political solution with unequivocal participation from the Rohingyas.

“The violence, the extreme deprivation and the massive violations of human rights have fueled a crisis of grave international concern. The international community must honor its responsibilities and act. We stand in solidarity with the Rohingya and all the people of Myanmar in their hour of greatest need,” said UN Human Rights Commissioner Volker Türk.

In the eight years since over 750,000 Rohingyas fled persecution and crossed the border into Bangladesh, the international community has had to deal with one of the most intense refugee situations in living memory. Attendees at the conference spoke on addressing the root causes that led to this protracted crisis—systematic oppression and persecution at the hands of Myanmar’s authorities and unrest in Rakhine State.

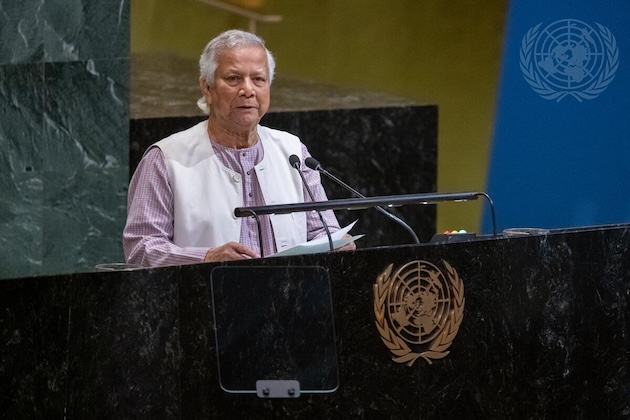

Muhammad Yunus, Chief Adviser of the interim Government of Bangladesh, addresses the high-level conference on the situation of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities in Myanmar. Credit: UN Photo/Manuel Elias

The military junta’s ascension in 2021 has only led to further unrest and instability in Myanmar and has made the likelihood of safe and sustained return far more precarious. Their persecution has only intensified as the Rohingya communities still residing in Rakhine find themselves caught in the middle of conflicts between the junta and other militant groups, including the Arakan Army.

At the opening of the conference, Rohingya refugee activists remarked that the systemic oppression predates the current crisis. “This is a historic occasion for Myanmar. But it is long overdue. Our people have suffered enough. For ethnic minorities—from Kachin to Rohingya—the suffering has spanned decades,” said Wai Wai Nu, founder and executive director of the Women’s Peace Network.

“It has already been more than eight years since the Rohingya Genocide was exposed. Where is the justice for the Rohingyas?” asked Maung Sawyeddollah, founder of the Rohingya Student Network.

For the United Nations, the Rohingya refugee crisis represents the dramatic impact of funding shortfalls on their humanitarian operations. UN Secretary-General António Guterres once said during his visit to the refugee camps in Bangladesh back in April that “Cox’s Bazar is Ground Zero for the impact of budget cuts”.

Funding cuts to agencies like UNICEF and the World Food Programme (WFP) have undermined their capacity to reach people in need. WFP has warned that their food assistance in the refugee camps will run out in two months unless they receive more funding. Yet as of now, the 2025 Rohingya Refugee Response Plan of USD 934.5 million is only funded at 38 percent.

Volker Türk, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, addresses the high-level conference of the General Assembly on the situation of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities in Myanmar. Credit: UN Photo/Manuel Elias

“The humanitarian response in Bangladesh remains chronically underfunded, including in key areas like food and cooking fuel. The prospects for funding next year are grim. Unless further resources are forthcoming, despite the needs, we will be forced to make more cuts while striving to minimize the risk of losing lives: children dying of malnutrition or people dying at sea as more refugees embark on dangerous boat journeys,” said Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

As the host country of over 1 million refugees since 2017, Bangladesh has borne the brunt of the situation. Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus said that the country faces its own development challenges and systemic issues with crime, poverty and unemployment, and has struggled to support the refugee population even with the help of aid organizations. He made a call to pursue repatriations, the strategy to ensure the safe return of Rohingyas to Rakhine.

“As funding declines, the only peaceful option is to begin their repatriation. This will entail far fewer resources than continuing their international protection. The Rohingya have consistently pronounced their desire to go back home,” said Yunus. “The world cannot keep the Rohingya waiting any longer from returning home.”

Along with the UN, Myanmar and Bangladesh, neighboring and host countries also have a role to play. Regional blocs like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are also crucial in supporting the Rohingya population as well as leading dialogues with other stakeholders across the region.

“In my engagements with Myanmar stakeholders, I have emphasized that peace in Myanmar will remain elusive until inclusive dialogue between all Myanmar stakeholders takes place,” said Othman Hashim, the special envoy of the ASEAN Chair on Myanmar. “For actions within Myanmar, the crucial first step is stopping the hostilities and violence. Prolonged violence will only exacerbate the misery of the people of Myanmar, Rohingya and other minorities included.”

“Countries hosting refugees need sustained support. Cooperation with UNODC [UN Office of Drugs and Crime], UNHCR, and IOM [International Organization for Migration] must be deepened,” said Sugiono, Indonesia’s foreign minister.

Supporting the Rohingya beyond emergency and humanitarian needs would also require investing resources in education and employment opportunities. Involved parties were encouraged to support resettlement policies that would help communities secure livelihoods in the long-term, or to extend opportunities for longterm work, like in Thailand where they recently granted long-staying refugees the right to work legally in the country.

“Any initiative for the Rohingya without Rohingya in the camp, from decision making to nation-building is unsustainable and unjust. The UN must mobilize resources to empower Rohingya. We are not only victims; we have the potential to make a difference,” said Sawyeddollah.

As one of the few Rohingya representatives present that had previous lived in the camps in Cox’s Bazaar, Sawyeddollah described the challenges he faced in pursuing higher education when he applied to over 150 universities worldwide but did not get into any of them. He got into New York University with a scholarship, the first Rohingya refugee to attend. He reiterated that universities had the capacity to offer scholarships to Rohingya students, citing the example of the Asian University of Women (AUW) in Chittagong, Bangladesh, where it has been offering scholarships to Rohingya girls since at least 2018.

The conference called for actionable measures that would address several key areas in the Rohingya refugee situation. This includes scaling up funding for humanitarian aid in Bangladesh and Myanmar, and notably, pursuing justice and accountability under international law. Türk and other UN officials reiterated that resolving the instability and political tensions in Myanmar is crucial to resolving the refugee crisis.

Kyaw Moe Tun, Permanent Representative of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar to the UN, blamed the military junta for the country’s current state and called for member states to refuse supporting the junta politically or financially. “We can yield results only by acting together to end the military dictatorship, its unlawful coup, and its culture of impunity. At a time when human rights, justice and humanity are under critical attack, please help in our genuine endeavour to build a federal democratic union that rooted in these very principles.”

IPS UN Bureau Report