Civil Society, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Global, Headlines, Humanitarian Emergencies, Migration & Refugees, TerraViva United Nations

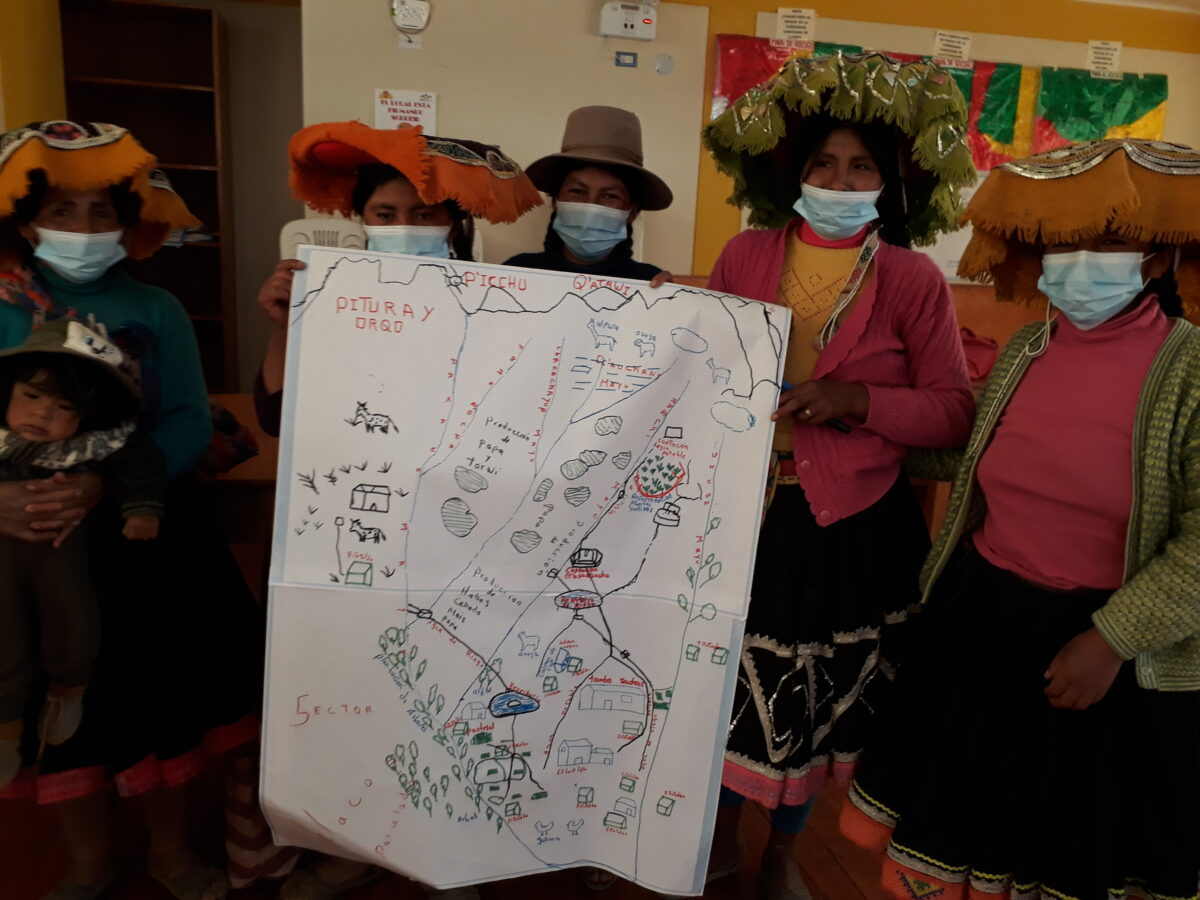

Families carry their belongings through the Zosin border crossing in Poland after fleeing Ukraine. Credit: UNHCR/Chris Melzer

– Russia’s brutal and devastating invasion of Ukraine has triggered the largest and fastest refugee movement in Europe since World War II. After only a single week, more than one million people had already fled the country.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) initially predicted that as many as four million people would flee; the UN now thinks that some 10 million will eventually be displaced.

While the EU calls this the largest humanitarian crisis that Europe has witnessed in “many, many years,” it is important to remember that it was not so long ago that the continent faced another critical humanitarian challenge, the 2015 refugee “crisis” spurred by the conflict in Syria.

But the starkly different responses that Europe has directed at these two situations—in addition to its draconian response to ongoing African migration across the Mediterranean—provide a cautionary lesson for those hoping for a more humane, generous Europe.

These differences also help explain why some of those fleeing Ukraine—in particular, nationals from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East—are not receiving the same generous treatment as the citizens of Ukraine.

Ukraine’s neighbours have thus far responded with an outpouring of public and political support for the refugees. Political leaders have said publicly that refugees from Ukraine are welcome and countries have been preparing to receive refugees on their borders with teams of volunteers handing out food, water, clothing, and medicines.

Slovakia and Poland have said that refugees fleeing the war in Ukraine will be allowed to enter their countries even without passports, or other valid travel documents; other EU countries, such as Ireland, have announced the immediate lifting of visa requirements for people coming from Ukraine.

Across Europe, free public transport and phone communication is being provided for Ukrainian refugees. On 3 March, the EU voted to activate the Temporary Protection Directive, introduced in the 1990’s to manage large-scale refugee movements during the Balkans crisis.

Under this scheme, refugees from Ukraine will be offered up to three years temporary protection in EU countries, without having to apply for asylum, with rights to a residence permit and access to education, housing, and the labour market.

The EU also proposed simplifying border controls and entry conditions for people fleeing Ukraine. Ukrainian refugees can travel for 90 days visa-free throughout EU countries, and many have been moving on from neighbouring countries to join family and friends in other EU countries. Throughout Europe, the public and politicians are mobilizing to show solidarity and support for those fleeing Ukraine.

This is how the international refugee protection regime should work, especially in times of crisis: countries keep their borders open to those fleeing wars and conflict; unnecessary identity and security checks are avoided; those fleeing warfare are not penalized for arriving without valid identity and travel documents; detention measures are not used; refugees are able to freely join family members in other countries; communities and their leaders welcome refugees with generosity and solidarity.

But we know that this is not how the international protection regime has always operated in Europe, particularly in those same countries that are now welcoming refugees from Ukraine.

Public discourse in Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and Romania is often tainted by racist and xenophobic rhetoric about refugees and migrants, in particular those from Middle Eastern and African countries, and they have adopted hostile policies like border push-backs and draconian detention measures.

A case in point is Hungary: The country has refused to admit refugees from non-EU countries since the 2015 “refugee crisis.” Prime Minister Victor Orbán has described non-European refugees as “Muslim invaders” and migrants as “a poison,” claiming that Hungary should not accept refugees from different cultures and religions to “preserve its cultural and ethnic homogeneity.”

In May 2020, The European Court of Justice found that Hungary’s arbitrary detention of asylum seekers in transit zones on its border with Serbia was illegal.

Hungary was not alone in its harsh response to the 2015 “crisis.” In their book Immigration Detention in the European Union: In the Shadow of the “Crisis” (Springer 2020), Global Detention Project (GDP) researchers detailed the evolution of the detention systems of all EU Members States before, during, and after the 2015 refugee crisis.

Among their key findings: During the years leading up to 2015, migration-related detention had largely plateaued across the EU, but refugee pressures spurred important increases in detention regimes across the entire region, which remained in place long after the “crisis” had subsided.

Fuelling these increases was anti-migrant rhetoric that spread from Brussels across the entire continent, abetted by EU-wide migration directives that allowed for lengthy detention periods. Then-European Council President Donald Tusk argued at that time that all arriving refugees could be detained for up to 18 months, in line with the limits in EU directives, while their claims were processed.

More recently, in late 2021, the terrible treatment of migrants and asylum seekers, most of them from Iraq and Afghanistan, trapped on Belarus’s borders with Poland and Lithuania sparked outrage across Europe. Belarus was accused of weaponizing the plight of these people, luring them to Belarus in order to travel on to EU countries as retaliation against EU sanctions.

Polish border guards were brutal in their treatment of these refugees and migrants, many of whom sustained serious injuries from Polish and Belarussian border guards. Thousands were left stranded in the forests between the two countries in deplorable conditions with no food, shelter, blankets, or medicines: at least 19 migrants died in the freezing winter temperatures.

In response to this situation, Poland sent soldiers to its border, erected razor-wire fencing, and started the construction of a 186-kilometre wall to prevent asylum seekers entering from Belarus. It also adopted legislation that would allow it to expel anyone who irregularly crossed its border and banned their re-entry.

Even before the stand-off between Poland and Belarus, refugees in Poland did not receive a warm welcome. Very few asylum seekers were granted refugee status (in 2020 out of 2,803 applications, only 161 were granted refugee status) and large numbers of refugees and migrants were detained: a total of 1,675 migrants and asylum seekers were in detention in January 2022, compared to just 122 people during all of 2020.

With this recent history as backdrop, the double standards and racism inherent in Europe’s refugee responses are glaring. There are no calls from Brussels today to detain refugees fleeing Ukraine for up to 18 months.

Why? Because, as Bulgarian Prime Minister Kiril Petkov said recently about people from Ukraine: “These are not the refugees we are used to. … These people are Europeans. … These people are intelligent, they are educated people. … This is not the refugee wave we have been used to, people we were not sure about their identity, people with unclear pasts, who could have been even terrorists.”

Similarly, Hungary’s Orban has said that every refugee coming from Ukraine will be “welcomed by friends in Hungary,” adding that one doesn’t have to be a “rocket scientist” to see the difference between “masses arriving from Muslim regions in hope of a better life in Europe” and helping Ukrainian refugees who have come to Hungary because of the war.

Sadly, these double standards have reared in the response to non-Ukrainians fleeing the war in Ukraine. There are a growing number of accounts of students and migrants from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia who have faced racist treatment, obstruction, and violence trying to flee Ukraine.

Many described being prevented from boarding trains and buses in Ukrainian towns while priority was given to Ukrainian nationals; others described being aggressively pulled aside and stopped by Ukrainian border guards when trying to cross into neighbouring countries.

There are also accounts of Polish authorities taking aside African students and refusing them entry into Poland, although the Polish Ambassador to the UN told a General Assembly meeting on 28 February that assertions of race or religion-based discrimination at Poland’s border were “a complete lie and a terrible insult to us.”

He asserted that “nationals of all countries who suffered from Russian aggression or whose life is at risk can seek shelter in my country.” According to the Ambassador, people from 125 different nationalities have been admitted into Poland from Ukraine.

Several African leaders have strongly criticized the discrimination on the borders of Ukraine, saying everyone has the same right to cross international borders to flee conflict and seek safety.

The African Union stated that “reports that Africans are singled out for unacceptable dissimilar treatment would be shockingly racist and in breach of international law,” and called for all countries to “show the same empathy and support to all people fleeing war notwithstanding their racial identity.”

Similar messages were shared by the UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, who said in a Tweet: “I am grateful for the compassion, generosity and solidarity of Ukraine’s neighbours who are taking in those seeking safety. It is important that this solidarity is extended without any discrimination based on race, religion or ethnicity,” and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees who stressed that “it is crucial that receiving countries continue to welcome all those fleeing conflict and insecurity—irrespective of nationality and race.”

The Ukraine refugee crisis presents Europe with not only an important opportunity to demonstrate its generosity, humanitarian values, and commitment to the international refugee protection regime; it is also a critical moment of reflection: Can the peoples of Europe overcome their widespread racism and animosity and embrace the universalist spirit of the 1951 Refugee Convention?

As Article 3 of the Convention holds, all member states “shall apply the provisions of this Convention to refugees without discrimination as to race, religion or country of origin.”

Rachael Reilly and Michael Flynn are based at the Global Detention Project in Geneva.