Civil Society, Democracy, Featured, Gender, Global, Headlines, Human Rights, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, TerraViva United Nations

Credit: UN Women

– The UN agency, which advocates women’s rights and gender empowerment, has predicted that gender equality is “300 years away.”

Addressing the UN Commission on the Status of Women last March, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres not only quoted the estimates provided by UN Women but also warned that progress toward gender equality is “vanishing before our eyes.”

“Women’s rights are being abused, threatened and violated around the world,” he said.

But a new report — the 2023 fourth edition of the global Women Peace and Security Index (WPS Index)—released October 24 draws on recognized data sources to measure women’s inclusion, justice, and security in 177 countries—covering over 99% of the world’s population.

“No country performs perfectly on the WPS Index and the results reveal wide disparities across countries, regions, and indicators. The WPS Index offers a tool for identifying where resources and accountability are needed most to advance women’s status – which benefits us all”, says the report.

India passes law to reserve seats for women legislators

4 OCTOBER 2023

The Index finds that societies where women are doing well are also more peaceful, democratic, prosperous, and better prepared to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Denmark leads the 2023 rankings as the top country to be a woman, scoring more than three times higher than Afghanistan which is at the bottom.

Afghanistan ranks worst of 177 countries– in terms of the status of women, according to this year’s Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Index launched in New York.

The five highest ranking countries were Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, Finland and Luxembourg. And the five lowest ranking countries were Afghanistan, Yemen, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan.

Published by Georgetown University’s Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS) and the Centre on Gender, Peace and Security at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, the WPS Index uses 13 indicators to measure women’s status, ranging from education and employment to laws and organized violence.

The United States ranks 37th this year, scoring similarly to Slovenia, Bulgaria and Taiwan in the second quintile.

Dr. Purnima Mane. Ex- President and CEO of Pathfinder International, and former Deputy Executive Director (Program) of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), told IPS the WPS Index emphasizes the sobering realities which different sectors of society –- including academic institutions, the United Nations, the media and civil society in general – have emphasized repeatedly over the years:

She said many countries which rank low in women’s status continue to remain so over time, despite global advocacy for gender equality

“Growing conflict and lack of security in countries could even worsen the situation for women and will not ensure adequate results in our efforts to boost women’s status. The relationship between peace and security and women’s overall wellbeing remains critical and demands adequate attention and investment.”

Data from the WPS Index, funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs show evidence of this relationship between peace and security and women’s status.

A clear example is the countries that rank high and low in this Index –not surprisingly the countries that rank low in women’s status are the very same countries in which peace and security are at an abysmally low level, she added.

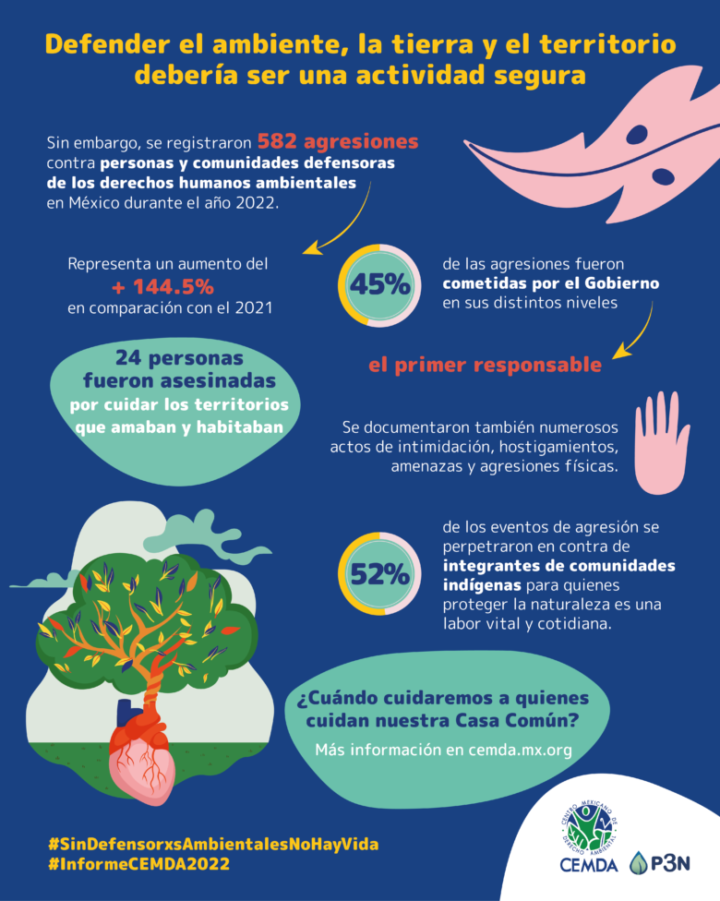

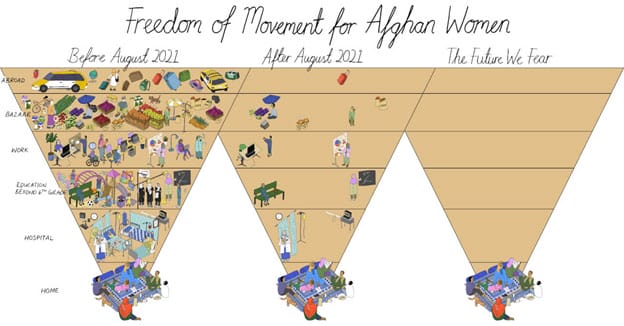

Sanam Anderlini, Founder/CEO of the International Civil Society Action Network (ICAN)* told IPS according to the index, in 2017, Afghanistan was ranked 152 out of 153 countries, with Syria coming last.

In 2019/2020, it was 16th out of 167, with Yemen coming last, and now in 2023, Afghanistan is coming at the bottom of the index.

‘This indicates that Afghan women were facing a long struggle even prior to the Taliban, but given that 60% of Afghans were under the age of 25, and many young women were in universities and entering professions including law, medicine and education, there was hope that the country’s overall ranking could also improve over time.’

She pointed out that Taliban’s takeover has set them on a downward generational spiral. The tragedy is that this decline was a result of the US’s loss to the Taliban at the negotiating tables in Doha.

“It is a result of the diplomatic community’s unwillingness to heed the warnings of Afghan women about the Taliban, or uphold their own commitments to the women peace and security agenda’s first tenet — the participation of women in peace processes.”

“But despite the darkness, we cannot forsake and forget Afghan women and girls. They are still fighting and finding ways to access education, healthcare and livelihoods,” said Anderlini.

“Now, more than ever, the international community must double down on engaging them and ensuring they are present and fully participating in the decision-making pertaining to the future of their country — not only in the humanitarian space, but also on economic, social and political and security matters. There are plenty of Afghan women – inside and outside the country — ready to take on this challenge,” she declared.

Elaborating further, Dr Mane said a range of reports prepared by a variety of sources, including the UN and academic institutions have been referenced in this Index using 13 different indicators on women’s status, to show that societies where women’s economic, social, and political situation, formal and informal justice for women, and the status of the security of women at the social and community level are doing well, are the very same societies, which overall, are more peaceful, economically stronger, have more democratic systems in place and are also dealing better with the impacts of climate change.

The WPS Index and its data, she pointed out, identify clearly areas where further investment is needed to boost women’s status. But what about general conflict and lack of security which adversely impact women particularly hard, along with others who are marginalized in different societies?

“The Index clearly demonstrates that all of the bottom 20 countries have experienced war and armed conflict of some sort, between 2021 and 2022 with more than half the women living in or near zones of conflict”.

With armed conflict growing in many countries over the last few years and the continuation of a generally negative climate in terms of women’s status in several countries such as Afghanistan, she argued, one cannot hope for a change in the status quo for women unless countries take a hard look at their policies and investments in both national peace and security and in women’s status.

“Any real change is possible only if the world acknowledges that the link between the two is critical, and paying attention to both is vital for improvements in national wellbeing as well as gender equality”, said Dr Mane, a former UN Assistant-Secretary-General (ASG) and an internationally recognized expert on gender, population and development, and public health, and who has devoted her career to advocating for population and development issues and working on sexual and reproductive health.

“With its scores, rankings, and robust data, the WPS Index offers a valuable tool for people working on issues of women, peace, and security,” said Elena Ortiz, the lead author of the WPS Index.

“Policymakers can use it to pinpoint where resources are needed. Academics can use it to study trends within indicators and across regions. Journalists can use it to give context and perspective to their stories. And activists can use it to hold governments accountable for their promises on advancing the status of women.”

All of the bottom 20 countries on this year’s Index have experienced armed conflict between 2021 and 2022. In most of these countries, more than half of women live in close proximity to conflict.

“Since 2021, Afghanistan has ranked the worst in the world to be a woman. Afghan women wake up each day to no jobs, no education and no autonomy over their lives. This report should serve as a wakeup call to world leaders that a nation of women is imprisoned.” said Torunn L. Tryggestad, Director of the Peace Research Institute Oslo’s Centre for Gender, Peace and Security.

IPS UN Bureau Report