Biodiversity, Civil Society, Development & Aid, Economy & Trade, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Food & Agriculture, Green Economy, Headlines, Integration and Development Brazilian-style, Latin America & the Caribbean, Projects, Regional Categories, TerraViva United Nations, Water & Sanitation

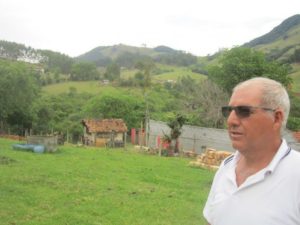

Elias Cardoso is proud of the restored forests on his 67-hectare farm, where he has protected and reforested a dozen springs as well as streams. “I was a guinea pig for the Water Conservator project, they called me crazy,” when the mayor’s office was not yet paying for it in Extrema, a municipality in southeastern Brazil. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

– “They called me crazy” for fencing in the area where the cows went to drink water, said Elias Cardoso, on his 67-hectare farm in Extrema, a municipality 110 km from São Paulo, Brazil’s largest metropolis.

“I realized the water was going to run out, with cattle trampling the spring. Then I fenced in the springs and streams,” said the 60-year-old rancher. “But I left gates to the livestock drinking areas.”

Cardoso was a pioneer, getting the jump on the Water Conservancy Project, launched by the local government in 2005 with the support of the international environmental organisation The Nature Conservancy and the Forest Institute of the southeastern state of Minas Gerais, where Extrema, population 36,000, is located at the southern tip.

The project follows the fundamentals of the National Water Agency‘s Water Producer Programme, which focuses on different ways to preserve water resources and improve their quality, such as measures to conserve soil, preventing sedimentation of rivers and lakes.

But at the core of the project is the Payments for Environmental Services (PES), which in the case of Extrema compensate rural landowners for land they no longer use for crops or livestock, to restore forests or protect with fences.

The “Water Conservator” (Conservador das Águas) began operating in 2007, with contracts offered by the PES to farmers who reforest and protect springs, riverbanks and hilltops, which are numerous in Extrema because it is located in the Sierra de Mantiqueira, a chain of mountains that extends for about 100,000 square km.

“Then everyone jumped on board,” Cardoso said, referring to the project in the Arroyo das Posses basin, where he lives and where the environmental and water initiative began and had the biggest impact.

View of the new landscape in the hilly area around Extrema, after the reforestation of thousands of hectares in three basins in this municipality in southeastern Brazil, where the local government has fomented the process of recovery by paying landowners for environmental services. The priority is to restore the forests at the headwaters of the rivers and on hilltops and protect them with cattle fences. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

In the 14 years since it was launched, the project has only worked fully in three basins, where two million trees were planted and close to 500 springs were protected. It is now being extended to seven other watersheds.

“The goal is to reach 40 percent of forest cover with native species” in the municipality and “so far we already have 25 percent covered, and 10 percent is thanks to the Water Conservator,” said Paulo Henrique Pereira, promoter of the project as Environment Secretary in Extrema since 1995.

“Planting trees is easy, creating a forest is more complex,” the 50-year-old biologist told IPS, stressing that it’s not just about planting trees to “produce” and conserve water.

The project began with the prospecting of areas and the training of technicians, after the approval of a municipal PES statute, since there is no national law on remunerated environmental services.

“The bottleneck is that there is no skilled workforce” to reforest and implement water conservation measures, Pereira said.

The project now has its own nursery for the large-scale production of seedlings of native tree species, to avoid the past dependence on external acquisitions or donations, which drove up costs and made planning more complex.

Since 2005 Paulo Henrique Pereira, Secretary of Environment in Extrema since 1995, has promoted the Water Conservator Project, which has won national and international awards for its success in recovering and preserving springs and streams, by paying for environmental services to rural landowners who reforest in this municipality in southeastern Brazil. “Planting trees is easy, creating a forest is more complex,” he says. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

The success of Extrema’s project, which has won dozens of national and international good practice awards, “is due to good management, which does not depend on the continuity of government,” said the biologist, although he admitted that it helped that he had been in the local Secretariat of the Environment for 24 years and that the mayors were of the same political orientation.

“It is a well-established project that is not likely to suffer setbacks,” he said.

The fact that the project offers both environmental and economic benefits helps keep it alive.

“My grandfather, who spent his life deforesting his property, initially rejected the project. It didn’t make sense to him to plant the same trees he had felled to make pasture for cattle,” said Aline Oliveira, a 19-year-old engineering student who is proud of the quality of life achieved in Extrema.

“When I was a girl, I didn’t accept the idea of protecting springs to preserve water either. I thought it was absurd to plant trees to increase water, because planting 200 or 300 trees would consume a lot of water. That was how I used to think, but then in practice I saw that springs survived in intact forest areas,” she said.

Later, when the PES arrived in the area, her grandfather gave in and more than 10 springs on the 112-hectare farm were reforested and protected. The payment is 100 municipal monetary units per hectare each year, currently equivalent to about 68 dollars.

Aline Oliveira studies engineering and lives on her family’s farm in southeastern Brazil. She is proud of the way life has improved in Extrema, a process that began with the establishment of the Payments for Environmental Services system, which guarantees income to farmers and ranchers for reforesting watersheds. It is a secure income at a time of falling milk prices and in a town far from the dairy processing plants. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

“The PES is a secure income, while milk prices have dropped, and everything has become more expensive than milk in the last 10 years. In addition, there were losses due to lack of transportation, since there is no major dairy processing plant within 50 km,” she told IPS.

Thanks to the municipal payments, “we were able to invest in cows with better genetics, buy a milking parlor and improve health care for the cattle, thus increasing productivity,” which compensated for the reduction in pastures, added the student, who works for the project.

The programme coincided with a major improvement in the economy and quality of life in Extrema. “I was born in Joanópolis, where there were better hospitals than in Extrema. But now it’s the other way around” and people from there come to Extrema, 20 km away, for heath care, Oliveira said.

This is also due to the industrialisation experienced by Extrema in recent decades, which becomes evident during a walk around the town, where many new industrial plants can be seen.

The water conservation project has also contributed to the water supply for a huge population in the surrounding area.

Arlindo Cortês, head of environmental management at Extrema’s Secretariat of the Environment, stands in the nursery where seedlings are grown for reforestation in this municipality in southeastern Brazil. “Building reservoirs does not ensure water supply if the watershed is deforested, degraded, sedimented. There will be floods and water shortages because the rainwater doesn’t infiltrate the soil,” he explains. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

The Jaguari River, which crosses Extrema, receives water from fortified streams and increases the capacity of the Jaguari reservoir, part of the Cantareira system, which supplies 7.5 million people in greater São Paulo, one-third of the total population of the metropolis.

“If the watersheds are deforested, degraded and sedimented, merely building reservoirs solves nothing,” said Arlindo Cortês, the head of environmental management at Extrema’s Secretariat of the Environment.

Extrema’s efforts have translated into local benefits, but contributed little to the water supply in São Paulo, partly because it is over 100 km away, said Marco Antonio Lopez Barros, superintendent of Water Production for the Metropolitan Region at the local Sanitation Company, Sabesp.

“No increase in the capacity of the Cantareira System has been identified since the 1970s,” he said in an interview with IPS.

“Thousands of similar initiatives will be necessary” to actually have an impact in São Paulo, because of the level of consumption by its 22 million inhabitants, he said, adding that improvements in basic sanitation in cities have greater effects.

São Paulo experienced a water crisis, with periods of rationing, after the 2014 drought in south-central Brazil, and faces new threats this year, as it has rained less than average.

Extrema also felt the shortage. “Since 2014 we have only had weak rains,” said Cardoso. The problem is the destruction of forests by the expansion of cattle ranching in the last three decades.

“The creek where I used to swim has lost 90 percent of its water. The recovery will take 50 years, the benefits will only be felt by our children,” he said.