Africa, Biodiversity, Climate Action, Climate Change, Climate Change Finance, Climate Change Justice, Conferences, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Food and Agriculture, Headlines, Humanitarian Emergencies, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

Africa needs approximately USD 579.2 billion in adaptation finance over the period 2020 to 2030, and yet the current adaptation flows are five to 10 times below estimated needs.

This goat died of starvation while surrounded by an inedible invasive plant. Lives hang in the balance as Kenya’s dryland is ravaged by a severe prolonged drought. Credit: Joyce Chimbi/IPS

– As thousands convene in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, for the Africa Climate Summit, the first time the African Union has summoned its leaders to solely discuss climate change under the theme ‘Driving Green Growth and Climate Finance Solutions for Africa and the World’, the backdrop is a country on the frontlines of a climate crisis.

The severe, sharp effects of climate change are piercing the very heart of an economy propped up by rainfed agriculture and tourism – sectors highly susceptible to climate change. After five consecutive failed rainy seasons, more than 6.4 million people in Kenya, among them 602,000 refugees, need humanitarian assistance – representing a 35 per cent increase from 2022.

It is the highest number of people in need of aid in more than ten years, says Ann Rose Achieng, a Nairobi-based climate activist. She tells IPS that Kenya is hurtling full speed towards a national disaster in food security as “at least 677,900 children and 138,800 pregnant and breastfeeding women in Kenya’s arid and semi-arid regions alone are facing acute malnutrition. Nearly 70 per cent of our wildlife was lost in the last 30 years.”

Despite Kenya contributing less than 0.1 per cent of the global greenhouse gas emissions per year, the country’s pursuit of a low carbon and resilient green development pathway produced a most ambitious Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to cut greenhouse gasses by 32 per cent by 2030 in line with the Paris Agreement.

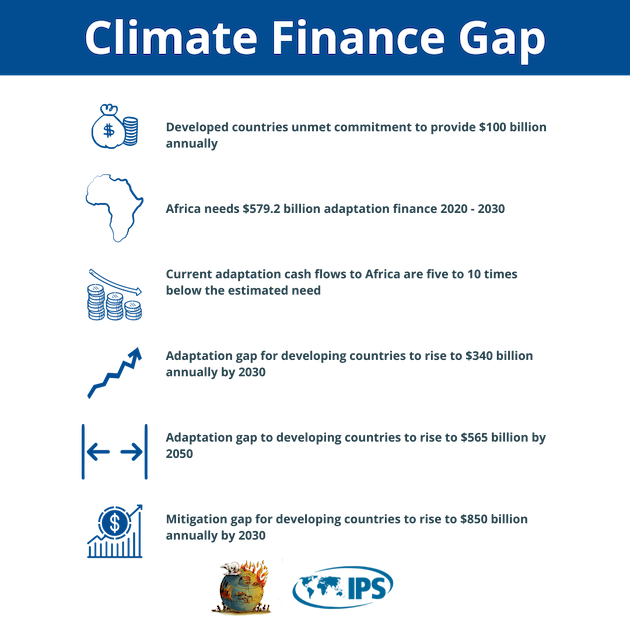

But as is the case across Africa, there are no funds to actualise these lofty ambitions. Africa needs approximately USD 579.2 billion in adaptation finance over the period 2020 to 2030, and yet the current adaptation flows to the continent are five to ten times below estimated needs. Globally, the estimated gap for adaptation in developing countries is expected to rise to USD 340 billion per year by 2030 and up to USD 565 billion by 2050, while the mitigation gap is at USD 850 billion per year by 2030.

After five consecutive failed rainy seasons, food insecurity is expected to escalate as maize crop has failed to flourish due to erratic weather patterns. Credit: Joyce Chimbi/IPS

As dams and rivers dry up, Kenya will continue to be on the frontlines of a climate crisis unless climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts are escalated. Credit: Joyce Chimbi/IPS

Frederick Kwame Kumah, Vice President of Global Leadership African Wildlife Foundation, tells IPS a big part of the problem is Africa’s burgeoning gross public debt which increased from 36 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to 71.4 per cent of GDP between 2010 and 2020 – a drag on its development progress and a disincentive for climate finance flows.

“There is a concern that climate finance, if and when provided, will be used to first service Africa’s debt burden. The first step to addressing Africa’s Climate Finance must be action towards debt relief for Africa. Freeing up debt servicing arrangements will release resources for continued development and climate finance purposes,” Kumah explains.

He says there is an urgent need to challenge the existing unfair paradigm for financing by developing countries. It is very expensive for developing countries to borrow for development purposes. Africa must then leverage its natural capital towards seeking innovative financing mechanisms such as green bonds and carbon credits to address its development and climate change challenges.

Nearly half, 23 out of 47 counties in Kenya, are classified as arid and semi-arid. Livelihoods are at risk as pastoralists are unable to cope with drastic weather changes. Credit: Joyce Chimbi/IPS

This waterfall is on the verge of drying up. Kenya’s economy is heavily dependent on tourism and agriculture. The two sectors are highly susceptible to climate change. Credit: Joyce Chimbi/IPS

“Climate finance was, as expected, a key part of COP27. It is a grave concern for Africa that developed countries’ commitment to provide $100 billion annually has yet to be met, even though the need for finance is becoming increasingly obvious. In COP27, we noted that new climate finance pledges were more limited than expected. Countries such as those in Africa are still waiting for previous pledges to be fulfilled,” says Luther Bois Anukur, Regional Director, IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

Meanwhile, Anukur tells IPS negotiations on important agenda items, most notably the new finance target for 2025, stalled. In COP27, Parties concentrated on procedural issues – deferring important decisions about the amount, timeframe, sources, and accountability mechanisms that may be relevant to a new finance goal in the future. African countries and many other vulnerable countries are in the fight for our lives, and sadly they are losing.

Anukur stresses that Africa’s natural resources are depleted, eroded, and biodiversity lost due to extreme effects of climate change leading to loss of lives and ecosystem services and damage to infrastructure at an alarming rate. Yet climate finance pledges have not materialised. The Africa Climate Summit should be the platform for Africa and developing partners to address existing finance gaps with clear programmatic and project approaches.

Africa must use the Summit to assess and prepare their position for the COP28 in the United Arab Emirates towards strengthening partnerships for the delivery of desired climate finance. Kumah adds that the principle of equal but differentiated responsibilities of nations must be adhered to for climate justice and to enable developing countries, who are least responsible for the effects of climate, to have much-needed resources to cope and adapt to biodiversity loss and climate change.

“In that respect, the creation of a dedicated funding mechanism to address loss and damage and another for adaptation and mitigation to redress historical and continued inequities in contributions towards biodiversity loss and climate change. We must rethink how private investments can be reshaped and harnessed for the benefit of biodiversity and climate action,” Kumah expounds.

“Private investments can be scaled through green bonds, carbon markets, sustainable agricultural, forestry and other productive sector supply chains. Transformative financing architecture is necessary at the domestic and international levels to bring the private and public sectors together to secure the critical backbone of Africa’s natural infrastructure.”

Climate finance gap. Graphic: Joyce Chimbi & Cecilia Russell

While developing countries submitted revised and ambitious National Adaptation Plans and NDCs as requested, Anukur says complicated processes to access financing for their climate actions persist. Stressing the need for reforming the international financial architecture, starting with multilateral development banks.

“The 2023 Summit for New Global Financing Pact held in Paris committed to a coalition of 16 philanthropic organizations to mobilize investment and support UN’s SDG priorities by unlocking new investment for climate action in low- and middle-income countries while reducing poverty and inequality,” Anukur observes.

Civil society organizations and activists such as Achieng have expressed concerns that such announcements are insufficient considering the scale of the challenges facing planet Earth. The Summit will have failed if the global financial architecture is not overhauled in line with the needs of the African continent, she says.

Anukur says the Summit must therefore propel Africa to new heights of climate financing to help reduce Africa’s vulnerability to climate change and increase its resilience and adaptive capacity in line with the Global Goal on Adaptation. Ultimately expressing optimism that the opportunity to unlock the potential of climate financing – breaking the shackles of debt and building a climate-resilient and prosperous Africa is, at last, in sight.

IPS UN Bureau Report