Civil Society, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Headlines, Latin America & the Caribbean, Poverty & SDGs, Regional Categories, TerraViva United Nations

Community-led environmental monitors actively protecting the Amazon Rainforest’s biodiversity as well as their livelihoods in Ushpayacu, Pastaza River basin, Peru. Credit: UNDP Peru/Susan Bernuy

– In August 31st 2021, five Nations including Costa Rica – the country where the Escazú Agreement was adopted – announced publicly working towards a proposal for UN Human Rights Council to recognize globally the right to a clean, safe, healthy and sustainable environment at its 48th session in September.

In a world where social-ecological crises are all too prevalent, do we need a broader human rights frame where also empathy and hope through legal innovation have a prevalent place? Can we imagine a world in which everyone can effectively engage in public participation and have access information and justice?

Latin America and Caribbean (LAC), like other parts of the world, face significant social-ecological challenges. In 2018, the UN Economic Commission of LAC estimated that around 185 million people lived in situation of poverty.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, these already high numbers are rising with more than one third of its 650 million population now living in poverty.

The pressures for healthy ecosystems in LAC range from climate change to pollution in land and water, and conversion of tropical forests to monoculture plantations. The LAC region presents a rising trend in major pressures on biodiversity with the highest proportion of threatened species on Earth.

Latin America – my home for many years – consistently tops the dire statistics of dangerous places to be an environmental human rights defender since Global Witness began to publish data in 2012.

Yet, there is also another story. A story of ordinary and courageous women and men, girls and boys. A story of empowered right-holders and responsible duty-bearers that day-to-day contribute to legal advances with a regional scope.

Vibrant grass-roots and civil society pushed and pulled in the negotiations of the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean (Escazú Agreement).

Their continued energy and collective action together with the legislative, executive and judiciary in their respective countries, will be vital for the Agreement’s implementation.

The Escazú Agreement – that weaves together human rights law and environment law – entered into force on Earth Day in 2021, and has a been ratified by half of its 24 signatory countries.

In the words of the Secretary-General of the United Nations “…this landmark agreement has the potential to unlock structural change and address key challenges of our times.”

Human rights are legally binding obligations that have contributed to precipitate societal transformations such as the recognition of indigenous peoples, peasants and local communities individual and rights across many Latin America and Caribbean countries.

In my work – which for the past twenty years has focused on human rights and environment – I have seen how degradation of healthy ecosystems afflicts specially the rights of people in vulnerable situations.

However, I have also witnessed first-hand how people in vulnerable situations including women environmental rights defenders are often those triggering change to safeguard the rich biological and cultural diversity in the region. This biocultural diversity provides essential contributions to the economy and livelihoods.

I believe that is just as important to place a spotlight in innovations and people’s agency in LAC countries as it is to report on catastrophic environmental and social events affecting the region.

While reading international media, I often find a single narrative of catastrophe associated with the LAC region or certain countries. In my view, this narrative risks creating distance rather than bringing people together, emphasising differences rather than our equal human dignity that is at the core of human rights.

Leaving no-one behind involves recognizing the agency of all and supporting everyone’s participation in caring for our planet.

Rather than a narrative of fear and despair of the global scale of environmental challenges, action implementing the Escazú Agreement connecting local and global instruments can generate positive change.

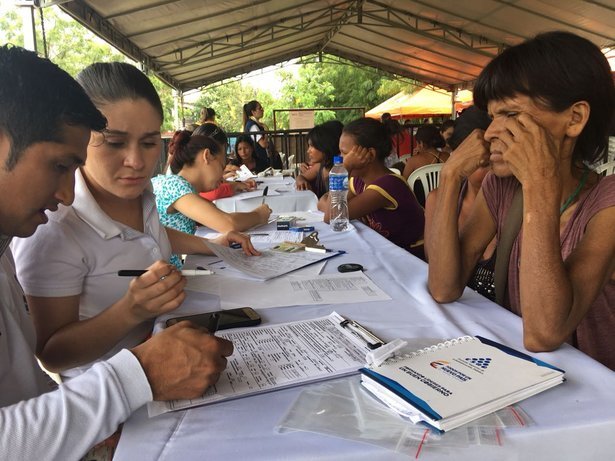

The Escazú Agreement can build on innovative governance instruments such as participatory environmental monitoring schemes – in which people not only access but also generate environmental information.

Transnational collaboration can also help, for example the 2021 EU Parliament Resolution which calls the EU Commission and EU member states to support countries to implement the Escazú Agreement.

The Escazú Agreement can also synergize with the post-2020 global biodiversity framework and National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans required by the Convention on Biological Diversity. Other instruments include National Action Plans aiming to implement the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).

Having already recognised the right to a healthy environment, the signatory Escazú Agreement countries have a historic opportunity to champion the global recognition of this right.

Already sixty nine States have endorsed a statement in favour of its by the Human Rights Council. Fifteen UN Agencies declared that “the time for global recognition, implementation, and protection of the human right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment is now”.

Complementary to the legal obligations that the Escazú Agreement generates, I consider that this agreement also provides an opportunity for right-holders and duty-bearers to place human rights narratives within a broader frame encompassing empathy and hope for present and future generations.

Strategically using legal innovations from the local to the global level can contribute to planetary stewardship and good quality of life in harmony with nature, leaving no-one behind.

Claudia Ituarte-Lima is a public international lawyer and scholar. She is researcher on international environmental law at Stockholm University, senior researcher at the Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law and visiting scholar at School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia. Ituarte-Lima holds a PhD from the University College London and a MPhil from the University of Cambridge. Twitter: CItuarteLima