Active Citizens, Africa, Climate Change, Climate Change Finance, Climate Change Justice, COP30, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Global, Headlines, International Justice, Latin America & the Caribbean, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

COP30 negotiator Malang Sambou Manneh believes the method of countering growth in fossil fuel development lies in technology. Showcasing alternatives that work provides the opportunity for the global South to take the lead and present best practices in renewables.

Climate change is a significant contributor to water insecurity in Africa. Water stress and hazards, like withering droughts, are hitting African communities, economies, and ecosystems hard. Credit: Joyce Chimbi/IPS

– The Gambia’s lead negotiator on mitigation believes that COP30 presents a unique opportunity to rebalance global climate leadership.

“This COP cannot be shrouded in vagueness. Too much is now at stake,” Malang Sambou Manneh says in an interview with IPS ahead of the climate negotiations. He identified a wide range of issues that are expected to define COP30 climate talks.

The global community will shortly descend on the Amazon rainforest, the world’s largest intact forest, home to more than 24 million people in Brazil alone, including hundreds of thousands of Indigenous Peoples. Here, delegates will come face-to-face with the realities of climate change and see what is at stake.

Malang Sambou Manneh.

COP30, the UN’s annual climate conference, or the Conference of Parties, will take place from November 10-21, 2025 in the Amazonian city of Belém, Brazil and promises to be people-centered and inclusive. But with fragmented and fragile geopolitics, negotiations for the best climate deal will not be easy.

Sambou, a lead climate negotiator who has attended all COPs, says a unified global South is up to the task.

He particularly stressed the need for an unwavering “focus on mitigation or actions to reduce or prevent greenhouse gas emissions.” Stating that the Mitigation Work Programme is critical, as it is a process established by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) at COP26 to urgently scale up the ambition and implementation of efforts to mitigate climate change globally.

Sambou spoke about how COP30 differs from previous conferences, expectations from the global South, fossils fuels and climate financing, stressing that “as it was in Azerbaijan for COP29, Belem will be a ‘finance COP’ because climate financing is still the major hurdle. Negotiations will be tough, but I foresee a better outcome this time round.”

The Baku to Belém Roadmap to 1.3T is expected to be released soon, outlining a framework by the COP 29 and COP 30 Presidencies for scaling climate finance for developing countries to at least USD 1.3 trillion annually by 2035.

Unlike previous conferences, COP30 focuses on closing the ambition gap identified by the Global Stocktake, a periodic review that enables countries and other stakeholders, such as the private sector, to take inventory to assess the world’s collective progress in meeting its climate goals.

The first stocktake was completed at COP28 in 2023, revealing that current efforts are insufficient and the world is not on track to meet the Paris Agreement. But while the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change, set off on a high singular note when it entered into force in November 2016, that unity is today far from guaranteed.

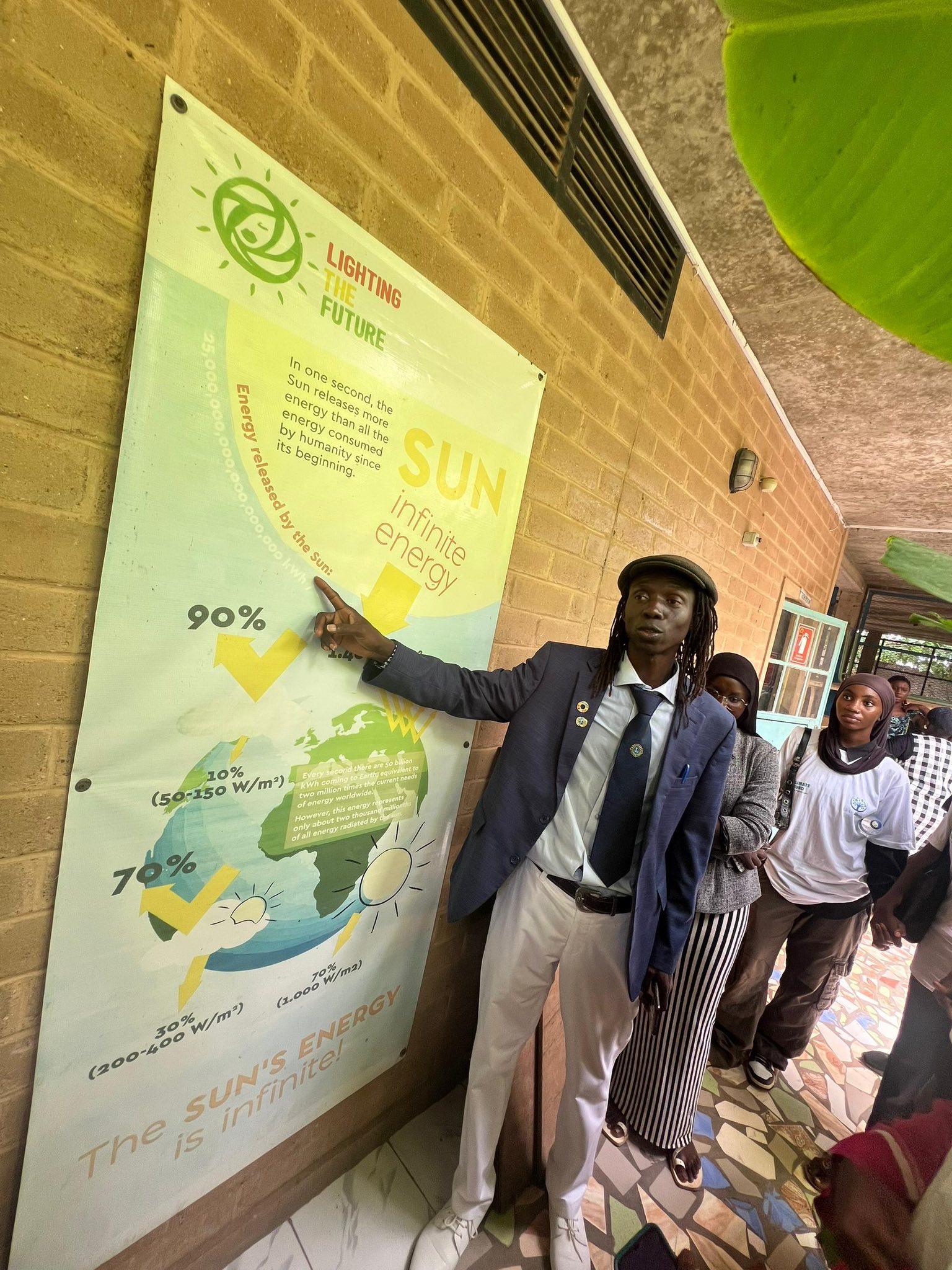

Malang Sambou Manneh with She-Climate Fellows. Credit: Clean Earth Gambia/Facebook

Unlocking high-impact and sustainable climate action opportunities amidst geopolitical turbulence was always going to be difficult. Not only did President Donald Trump pull the United States out of the Paris Agreement, but he is now reenergized against climate programs and robustly in support of fossil fuels—and there are those who are listening to his message.

Sambou says while this stance “could impact the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy, many more countries are in favor of renewable energy than against.”

“But energy issues are complex because fossil fuels have been a way of life for centuries, and developed countries leveraged fossil fuels to accelerate development. And then, developing countries also started discovering their oil and gas, but they are not to touch it to accelerate their own development and must instead shift to renewables. It is a complex situation.”

Ilham Aliyev, the President of Azerbaijan, famously described oil as a “gift from God” at COP29 to defend his country’s reliance on fossil fuels despite climate change concerns. This statement highlights the complexity of the situation, especially since it came only a year after the landmark COP28 hard-won UAE Consensus included the first explicit reference to “transitioning away from all fossil fuels in energy systems” in a COP agreement.

As a negotiator, Sambou says he is very much alive to these dynamics but advises that the global community “will not successfully counter fossil fuels by saying they are bad and harmful; we should do so through technology. By showcasing alternatives that work. This is an opportunity for the global South to take the lead and present best practices in renewables.”

And it seems there is evidence for his optimism. A recent report shows the uptake of renewables overtaking coal generation for the first time on record in the first half of 2025 and solar and wind outpacing the growth in demand.

This time around, the global south has its work cut out, as it will be expected to step up and provide much-needed leadership as Western leaders retreat to address pressing problems at home, defined by escalating economic crises, immigration issues, conflict, and social unrest.

It is in the developing world’s leadership that Sambou sees the opportunities—especially as scientific evidence mounts on the impacts of the climate crisis.

The World Meteorological Organization projects a continuation of record-high global temperatures, increasing climate risks and potentially marking the first five-year period, 2025-2029.

Sambou says all is not lost in light of the new and ambitious national climate action plans or the Nationally Determined Contributions.

This past September marked the deadline for a new set of these contributions, which will guide the COP30 talks. Every five years, the signatory governments to the Paris Agreement are requested to submit new national climate plans detailing more ambitious greenhouse gas emission reduction and adaptation goals.

“Ambition has never been a problem; it is the lack of implementation that remains a most pressing issue. Action plans cannot be implemented without financing. This is why the ongoing political fragmentation is concerning, for if there was ever a time to stand unified, it is now. The survival of humanity depends on it,” he emphasizes.

“Rather than just setting new goals in Belém, this time around, we are better off pushing for a few scalable solutions, commitments that we can firmly hold ourselves accountable to, than 200 pages of outcomes that will never properly translate into climate action.”

Despite many competing challenges and a step forward, two steps backwards here and there, from the heart of the Amazon rainforest, COP30’s emphasis on the critical role of tropical forests and nature-based solutions is expected to significantly drive action for environmental and economic growth.

Note: This interview is published with the support of Open Society Foundations.

IPS UN Bureau Report